I’m going to occasionally write short pieces on brief and sometimes unexpected encounters, of a religious or spiritual nature, that I’ve experienced over the course of what has turned out to be an unexpectedly long life.

SHAKTIPAT*

“She’s 144 years old and wheeled around on a dolly,” Andy exclaimed excitedly about the “Bruja” he’d heard of, “Very famous around here, a powerful healer.”

I was skeptical. Andy, our Mexican American buddy, was sometimes given to exaggeration, especially in regard to spiritual matters. The image of a 144 year old woman, a Bruja or witch, ensconced on a dolly, struck me as farfetched.

It was the spring of 1968 and we’d recently settled into Oaxaca in Southern Mexico, where we’d come in search of Hongos, the fabled “magic mushroom.”

Andy and my brother Paul had rented a small boxy concrete room that sat atop the corner of a fortress-like home enclosing a large inner courtyard with an impressive wooden, drive-through gate, which I’d nicknamed “Fort Apache.” They planned the trip long in advance, saving money and getting the necessary paperwork. When I decided on the spur of the moment to come along, they were kind enough to let me join them.

Andy and my brother Paul had rented a small boxy concrete room that sat atop the corner of a fortress-like home enclosing a large inner courtyard with an impressive wooden, drive-through gate, which I’d nicknamed “Fort Apache.” They planned the trip long in advance, saving money and getting the necessary paperwork. When I decided on the spur of the moment to come along, they were kind enough to let me join them.

I’d recently resolved to give away everything and become a homeless wanderer. A trip to Mexico seemed like a good start to life “on the road.” Without much in the way of money, I slept in the car Andy had purchased especially for the trip — a sweet, dark green and black, ’47 Chevy sedan.

When we hit the border at Nogales I worried they wouldn’t let me across without the proper papers but Andy assured me it would be OK. Sure enough, when he returned from a visit to the office on the Mexican side he told me, “They only want $5 to let you across.”

As we drove through the check point the officer stopped us, gesticulated towards me and spoke loudly in rapid Spanish, which Andy translated. “He says that for YOU they want $10.” I guessed that was because of my long hair and full beard — still a rarity outside of San Francisco. Andy and Paul had both cut their hair before embarking.

I didn’t know if I should be insulted or flattered at being worth twice as much with long hair and a beard. Throughout our trip through Mexico I would often be greeted with a hearty, “Heey Castro.”

After a few nights in Oaxaca, sleeping in the wide back seat of the Chevy, a rapping on the window interrupted my slumber. It was one of the comically attired local policemen, whose elaborate uniforms sported epaulets and ribbons reminiscent of turn-of-the-century European officers.

I sat bolt upright, fearful of what would be my punishment for sleeping in a parked car. The officer pointed to the lock button on the windowsill of the front door. I complied by lifting it to the unlocked position. He opened the door, put his nightstick on the floor, lay down on the front seat, and promptly went to sleep.

I guess I should have been relieved to have the law on my side, so to speak, but not only did he snore fitfully, he farted mightily, until the whole car reeked of recycled beans.

One morning I wandered away from the main part of town, along the dusty streets of the surrounding barrio. I reveled in the beauty of brightly colored adobe buildings fading in the southern sun. Walking alone in such unfamiliar surroundings brought me completely into the present, where I felt wonderfully open and alive.

At a wide intersection I stood pondering which direction to go in next. Suddenly, diagonally to my left at the far corner of the street, a young man appeared wheeling a dolly. Near the ground, on a small platform in front of the wheels, sat a wizened old woman whose legs were folded flat together and covered by a shawl or thin blanket. Except for a remarkable life-force that emanated from her she looked to be well over a hundred years old.

The young man and his unusual cargo stopped abruptly at the corner. As I gazed at them across the expanse of dusty street, the old woman smiled, put her thumb and forefinger together, and gently shook a gnarled hand in my direction — a gesture like a grandmother would make leaning over a crib to squeeze the cheek of a baby.

I was instantly overcome by a jolt of overpowering love, a love almost sexual in its blissful intensity, unlike anything I’d ever experienced.

In a haze of blinding light I staggered off down the street.

Later, along with a delicious warmth that lingered with me for days, I felt immense gratitude — even though I wasn’t sure exactly what it was she’d given me

*Shaktipat or Śaktipāta (Sanskrit, from shakti – “(psychic) energy” – and pāta, “to fall”) refers in Hinduism to the conferring of spiritual “energy” upon one person by another. Shaktipat can be transmitted with a sacred word or mantra, or by a look, thought or touch – the last usually to the ajna chakra or third eye of the recipient. Saktipat is considered an act of grace (anugraha) on the part of the guru or the divine. It cannot be imposed by force, nor can a receiver make it happen. The very consciousness of the god or guru is held to enter into the Self of the disciple, constituting an initiation into the school or the spiritual family (kula) of the guru. It is held that Shaktipat can be transmitted in person or at a distance.

BLOOD OF CHRIST

I’d always been fascinated with the Penitente Indians — Native Americans said to be indigenous to Mexico who converted to Christianity.

Isolated in the sparsely inhabited reaches of Northern New Mexico the Penitente developed their own austere form of Catholicism, noted for its ritual reenactment of the Passion of Christ on Good Friday. A procession of flagellants whipping and scourging their flesh, blood streaming down arms and torsos, accompany a young man chosen to carry the cross that year. The ritual is said to culminate in an actual crucifixion using sterilized steel nails. Thankfully the guest of honor is taken down from the cross before he actually dies.

When the mainstream church sought to interfere in their practices the Penitentes evolved into a secretive, mystical “Brotherhood.”

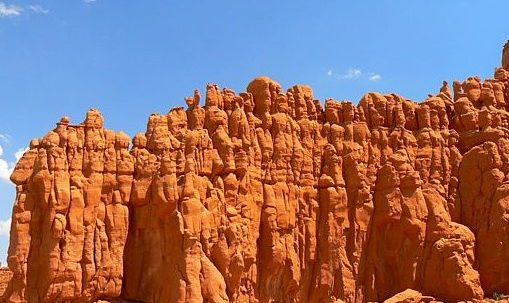

In the fall of 1968 I was hitchhiking around the Southwest, circling through Hopi and Navajo country, past false-front cowboy towns, through dusty barrios and along city streets of neon and concrete. Stone “Hoo Doo” people, embedded side by side in the rock walls of mesas like guardians carved in the pillars of Egyptian tombs, gazed down impassively as I went back and forth through Utah and Arizona.

I slept under freeways and bridges, in dry river beds beneath a star-strewn sky, and on park benches and picnic tables. Occasionally I was taken in by friendly people looking to get high with a real hippie, or if I got really lucky — a lonely woman to lie with in a darkened bedroom.

I was a prototype for the legion of homeless wanderers who would follow in the years to come — wild-eyed madmen wrestling with personal demons on city streets and roadsides. It was one long meditation, sometimes spent actually sitting cross-legged beside streams or in mountains. I stayed for a short time in an old mining cabin beside a small creek winding through a meadow high in the Colorado Rockies where I awoke in the morning to little chipmunks perched at the foot of the bed seeking handouts. For a few weeks I worked pitching hay bales on a ranch.

Finally I ended up in Penitente country north of Taos, hitchhiking on a back road across an elongated plateau, with the range of Sangre de Cristo Mountains holding up the sky to one side. A series of short rides took me through tiny settlements of scattered adobe houses, with old pickup trucks rusting under bare trees and dirty faced little kids staring wide eyed at the long haired bearded stranger in a tattered corduroy sports coat and old bluejeans. It was already October and the wind had a sharp cold edge to it.

Dropped off late in the afternoon at a desolate crossroads just south of the Colorado border, I gazed up apprehensively at the mountains slowly disappearing into ominous clouds and the sky growing darker. The main road, devoid of traffic and eerily empty, stretched out straight in both directions. Away from words and images to echo my feverish thoughts, my mind too became empty and calm.

After a few hours without a single vehicle driving by, I realized it was not only getting darker but much colder as well. Thin layers of icy snow started flying across the deserted roadway as an early blizzard blew in from the Northwest.

Far off in the distance a lone light flickered in a ranch house. For a brief instant my mind flew across the expanse of barren landscape and I gazed out through the eyes of a woman sitting inside by the fire.

The temperature dropped precipitously and low drifts of snow began to accumulate in a ditch by the roadside. Surprisingly, I didn’t feel cold. In fact I wasn’t feeling anything, except an overwhelming urge to fall asleep. The vision of a long dark tunnel opened up before me, with a glorious golden light at the end of it.

Just as I was getting ready to lie down in the snow by the side of the road, a baby blue and white ’55 Oldsmobile hardtop, exactly like one I once owned, pulled to a stop in front of me. For a moment I thought it might be an hallucination, but as I stumbled forward I saw three Indians, black hair and weathered faces under battered cowboy hats, staring expectantly at me. The door opened and they beckoned for me to get in the back seat.

As we rumbled off down the road they handed me a bottle of sweet red port to drink from, followed by a partially gnawed head of green cabbage to chomp. The port, a wine that I’d never tasted until then, warmed up my insides as it went down. It’s been a favorite of mine ever since — as is cabbage, which I prefer cooked, but tasted pretty good raw.

After a few pleasantries I discovered my saviors were Penitente Indians. They seemed pleased when I told them I’d always wanted to meet genuine Penitente. Once across the Colorado border we pulled into a big truck stop at a busy highway intersection. By then a cold rain was falling.

My companion in the back seat offered to buy me a drink at the tavern nearby. As we sat at the bar drinking whiskey and beer he told me he’d always wanted to meet a genuine hippy. “You look so much like Jesus,” he crooned while gently stroking my long hair. He said he’d taken LSD a few times and that I could stay at their place nearby and take it with them. The thought occurred to me that maybe they wanted to fatten me up for the “Ritual” in the spring. Although flattered, I wasn’t sure I really wanted to go there.

A psychedelic vision flashed before me of a smooth dirt floor inside ancient adobe walls, followed by a wave of paranoia as I remembered that the Indians of the Southwest had somehow determined that hippies were homosexuals. The thought of taking LSD with a band of horny Indians, who were also into bodily mortification, was even less appealing than the cold highway outside.

I downed my drink and thanked them for their kindness but said I really had to be on my way. They looked on with bemused expressions as I backed nervously out the door and quickly hitched a ride on a big rig truck going west towards Alamosa and Durango.

I’ve since read that dying of hypothermia (low body temperature) is actually quite pleasant, like falling peacefully asleep.

MEETING

“Treading the secret path, you shall find the shortest way.

Realizing emptiness, compassion will arise within your heart

Losing all differentiation between yourself and others, fit to serve others you shall be” Milarepa, at his death.

Mrs. Gretzinger’s tiny old Toyota Corolla hardly seemed capable of climbing the steep dusty road up out of Carmel Valley to Tasajara Hot Springs and the Zen Monastery that had recently been established there. The little car vibrated and jumped around as I drove us up over row after row of washboard ruts, around sharp corners (hoping we wouldn’t meet someone coming the opposite direction), until finally we reached the top of a high plateau, where panoramic views of blue ridges fading in the distance and the clear air made me imagine we were on a journey across Tibet.

It was the summer of 1971 and my friend Mrs. Gretzinger had taken it upon herself to make sure I got out of my little hermitage in the Sierra foothills in order to visit what she considered significant places and people. I teased her about being “spiritually promiscuous” because she was personally acquainted with every type of religious practice imaginable, from various, often exotic forms of Christianity, to psychics and yogis — and now Zen Buddhism.

As we drove along a ridge towards Tassajara she made me pull over by a huge very singular oak tree growing right on the edge of the road. The trunk looked to be over ten feet in diameter, with huge spreading branches.

Mrs. Gretzinger got out and circled the tree, lovingly caressing the rough bark and putting her face close to it. She had recently lost her job as a teacher in the tiny foothills town of Copperopolis because she had taken her grammar school class out to gather around a notable local oak tree and “listen to what it had to say.”

I think the townsfolk were already suspicious of her for visiting the hippy hermit (yours truly) who lived in the old pump house beside the pond outside of town. “Talking to trees” must have been the final straw.

She didn’t seem to mind losing her job and it hadn’t deterred her from continuing to converse not only with trees, but with various other denizens of the natural world. She said she was ready for retirement anyway and was about to take up permanent residence in her home at Capitola on the coast. Once there she would doff a little bikini every morning, her skinny old body wrinkled from sunbathing, walk down to the beach nearby, wade into the freezing water of the North Pacific and swim until she was out of sight, and then back in again.

I would miss her occasional visits. When she first hiked over the hill from where she rented a room from a local matron in Copperopolis and walked through the graveyard and down across the meadow to my door, I’d already been residing in my remote shack beside the old pond for several years.

I must have impressed her because not long after that first visit she brought another old lady with her, who was apparently wealthy and well-connected. They offered to set me up in an ashram for people to visit, where I could, presumably, impart some of my hard-earned wisdom.

I found the idea preposterous and laughable. Granted I’d been meditating and practicing yoga quite strenuously, but I’d only had one moment of real insight and that lasted just a few seconds. Although it was enough to keep me going it hadn’t left me with much real understanding.

Looking back I do think that my power of bare concentrated attention had developed to a higher degree than I realized because the offer to turn me into a guru didn’t engender the least bit of ego in me (as it probably would now) and I just laughed it off as absurd.

As we drove down the incredibly long steep grade into the narrow Tassajara Valley I was careful not to lean on the brakes too hard, lest our little car end up like the rusting vehicles in ditches along the roadside that conjured up images of dedicated seekers abandoning their disabled autos to rush into the monastery, never to come out again.

Once inside Tassajara Mrs. Gretzinger disappeared into the women’s side of the hot baths.

Left to my own devices I walked up Tassajara creek and found an isolated spot beside the rushing water to meditate. I especially like sitting beside a stream. The characteristic downward slope provides the same effect as sitting on a meditation cushion, with the added benefit of fresh air and sunshine.

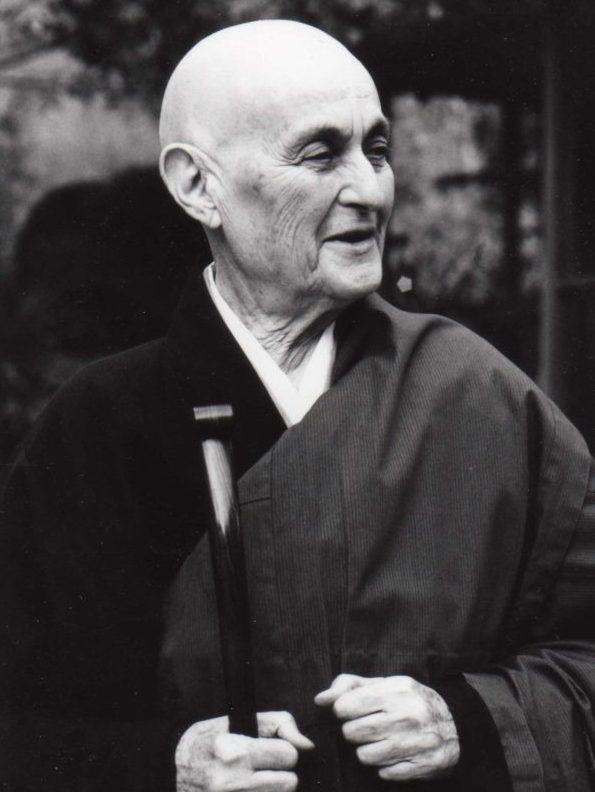

When we’d checked in at the office earlier I’d overheard that Suzuki Roshi was currently in residence. My inclination to sit zazen (meditation) whenever I was alone was given renewed purpose by the thought of his presence there.

I hadn’t seen him since my days in the Haight Ashbury, but he remained an ever-present inspiration. His simple method of counting and watching the breath and “just sitting” had informed my meditations ever since, and I intended someday to become his student.

I remembered how he spoke once of “really meeting someone.” He said that most of us had never actually “met” anyone, that what we thought of as meeting was not even close to what it was like to really meet someone.

Meditating beside the stream I had an intense vision of Suzuki sitting in zazen. I saw him from outside and inside simultaneously, like I was both myself and him at the same time. His life-stream flashed before my eyes, first in Japan, then coming to America, and finally right up to the present moment, as if he were running across time towards me.

I stood up and wandered downstream to the mineral baths. Along the wall at the entrance was a faded mural of a Native American chieftain cradling his daughter. Legend has it that the healing waters of Tassajara hot springs came gushing up out of the ground as a result of the chieftain’s tears and fervent prayers for his sick daughter who was dying as he carried her towards the ocean for healing.

I went into the main bath on the men’s side. The smooth plaster in the big hot pool was a unique turquoise blue characteristic of hot springs from the early part of the twentieth century when Tassajara and similar resorts had enjoyed great popularity. I marveled at the color and how whoever had built the baths had managed to create such a perfect hue, like the blue of the sky in landscape paintings from the same period.

I had the large bath all to myself. Between plunges into the fiery hot sulfurous water I was doing hatha yoga and meditating naked in the full lotus, my body flexible from the bath.

Suddenly a tall shaved-head monk entered the bathing area, holding a smoking stick of incense between raised palms. Following behind him was Suzuki Roshi.

I jumped up and asked if I was supposed to be there, or if it was the monks bathing time. The monk assured me it was OK and to just continue what I was doing. Then he left me alone with Suzuki.

I slid into the bath and looked up as Suzuki disrobed (literally) and somewhat awkwardly got into the hot water, one hand held politely over his genitals. With his small body and shaved head he reminded me of the little guys in Japanese wood block prints wearing breech-cloths and running with water buckets.

Neither of us spoke as we faced each other across the steaming water. Normally I’m shy and non-confrontational but there was something about Suzuki so calm and accepting that my agitation and anxiety quickly melted away.

The surroundings faded into a round orb of consciousness, like “seeing” with eyes relaxed in zazen. Suzuki was transparent. I could see right into his mind, except that it was my mind as well, a mind totally clear and open like empty space, free of all discrimination such as self and other, or teacher and student.

Since the experience was without images and thoughts, it’s difficult to remember or say much about it — even how long we remained that way.

The spell was finally broken when a feeling of deep suffering and pain arose and Suzuki abruptly got out of the bath and disappeared. I couldn’t be sure who’s pain it was, but since I’d recently been experiencing both physical and emotional pain, I assumed it was mine reflected back at me.

Later, as I drove away from Tassajara with Mrs. Gretzinger we stopped at the little spring on the side of the road. When I leaned over for a drink of cold water I had an urge to go back to Tassajara. Something told me this would be my last opportunity, that Suzuki would die soon.

No, I thought, that’s ridiculous, he had looked strong and healthy. I would wait until I felt ready and then I would return and become his student.

A few months later I learned he had died.

AFTERWARD

For Suzuki to engage with a wild-eyed stranger like myself on such an intimate level struck me as absolutely fearless and compassionate. He encountered me as an equal, though my foolishness must have been apparent. Even if I couldn’t see my own Buddha Mind, he could. There was no opposition in him, no need to dominate or instruct. Because of that openness, his influence was profound.

After Suzuki died I returned to Tassajara intent on finally becoming a member of the community and practicing zen there. Immediately upon arriving I approached a young man in the office and informed him of my intention.

“I’ll paint watercolors on location around the area, sell them and donate all the money to Tassajara to pay for my room and board,” I offered.

“You can’t do that,“ he said smiling benignly at my naivete. “Everyone here is assigned a job.”

“But I would be worth much more as an artist. They must need carpenters, plumbers, even lawyers. It seems a shame to let those skills go to waste.”

“Baker Roshi doesn’t want us to become attached to an identity like a job,” he said, referring to the new Abbot, Suzuki’s successor, “He even makes everyone rotate jobs periodically so they won’t become attached.”

“What about him, does he rotate his job periodically so he won’t become attached?”

He laughed, and that was that. Painting was more than just an ego-identity for me. It was a disciplined practice, like meditation. I wasn’t willing to give it up in order to put myself under the total control of someone whom I’d never met.

It would be over a decade before I returned to Tassajara again, this time for a week as a “work-study student” during the summer guest season. A fresh-faced and bright-eyed Reb Anderson, who would later replace a disgraced Richard Baker as Abbott, spoke to the assembled new guest students. He apologized for the laxity of the summer practice, hinting that it bore little relation to the real practice periods that took place during the winter when the guests were gone.

“Everyone comes to Buddhism by a different path, with a different story,” he said.

Assigned a bed at the end of a long dormitory that looked like it had once been a barn, I was somewhat distressed to discover a crack in the wooden wall right over my bed which was home to a nest of strange bees, the likes of which I’d never seen before — very large, fuzzy black, and longer than ordinary bumble bees. They made a loud buzzing noise as they zoomed back and forth to their crack in the wall just inches above me.

Several times during my week-long stay there, when I would try to catch a short nap during breaks in the schedule, one of the giant bees would somehow get under the covers with me and make a dreadful commotion, which sent me hurling out of bed. Incredibly they never stung me.

The toilets nearby, which were touted as some kind of cutting-edge technology, consisted essentially of a hole in the ground which one hung over and threw ashes in afterwards.

Despite these inconveniences, I took to it like a duck to water. The dark figures in robes floating silently up the path towards the Zendo in the faint early morning light, sitting upright in long rows listening to birds chirping and the sound of the creek flowing past, chopping vegetables in the kitchen with my hair tied up in a bandana as guests peered in awestruck at the sight a real monk at work, and especially the delicious vegetarian food — all helped open my mind to the streams of bliss flowing though that narrow valley.

I had taken a translation of Huang Po’s “Transmission of Mind” with me and when I visited the little Tassajara Library I discovered they didn’t have a copy. I located the librarian and offered to donate it to them but was politely rebuffed with the explanation that it wasn’t the proper school of zen.

So instead I gave the book to a pleasant young fellow who occupied the bunk across from mine. He was working on a medical degree at UC San Francisco. I told him of my encounter with Suzuki and explained that even though Huang Po was the teacher of Rinzai, the founder of a rival Zen school, his teachings were very similar to the Soto school and Suzuki.

At the end of the week we had some free time and I hiked up to a large rock that was a memorial to Suzuki Roshi placed over his ashes. When I approached, a little lizard scampered to the top of the massive stone and looked directly at me.

I remembered Suzuki’s kindness. Tears streamed down my face. Even without the opportunity to practice with him further, in that brief encounter he had shown me all I would ever need to know.

DATURA LADY

“…the external world is only a manifestation of the activities of the mind itself, and the mind grasps it as an external world simply because of the habit of discrimination and false reasoning.”

Lankavatara Sutra

In the late sixties, while I was living in a shack by a pond in the Sierra foothills, I visited my old buddy Mel and his new girlfriend, a slender little redhead. They were on a small secluded island in the Sacramento River Delta, in a ramshackle house hung out over the water’s edge on tall stilts that provided support for impressive spider webs woven by large yellow and black spiders, each sitting motionless in the center of her shining orb.

In the late sixties, while I was living in a shack by a pond in the Sierra foothills, I visited my old buddy Mel and his new girlfriend, a slender little redhead. They were on a small secluded island in the Sacramento River Delta, in a ramshackle house hung out over the water’s edge on tall stilts that provided support for impressive spider webs woven by large yellow and black spiders, each sitting motionless in the center of her shining orb.

A narrow, floating, wooden dock reached out into the placid green water where an old boat, which had deposited me there earlier, was tied up. It was not much more than a rowboat with an outboard motor on the back, but we went put-putting merrily around the delta channels that stretched out in every direction, the three of us sitting naked in the little boat with the hot summer sun beating down, occasionally stopping to jump into the river and swim around to cool off.

At the end of the day I walked with Mel to the garden behind the house to pick some vegetables for dinner. The center of the little island was lower than the perimeter on which their cottage rested. As we walked down the path we went past a round bush, almost as tall as myself, festooned with white trumpet-shaped flowers with soft yellow centers. When I passed close by the bush I felt a familiar psychic rush, which I immediately took to be an LSD flashback. Although I’d never experienced flashbacks, I’d been warned that someday I would.

“ What is that plant?” I asked Mel, “I felt like I got a hit of acid when we walked by it.”

What is that plant?” I asked Mel, “I felt like I got a hit of acid when we walked by it.”

He explained that it was a Datura bush grown from seeds he brought back from a trip to the Grand Canyon. He was teaching at an alternative high school and he took the kids on a field trip to the Colorado River Basin. They picked some leaves from Datura growing nearby and mixed it with hamburgers they barbequed at their campsite.

Mel said that after that things got really crazy, with real-looking people appearing out of rock formations and everyone hallucinating and staggering around. Some kids even fell into the river and he had to go in and pull them out.

“We were lucky no one died,” he exclaimed.

On the way back to the house I stopped at the bush, reached in and picked a green seed pod, about the size of a golf ball, with little spikes sticking out the sides that reminded me of the explosive floating mines used to destroy ships. I brought it with me when I returned to the foothills and placed it on a shelf over my desk, where it sat for several weeks.

Until one day…

I awoke that morning feeling like I wanted to get high and do yoga. I searched everywhere for some marijuana, but couldn’t even find a roach. Then my gaze fell on the seed pod on the shelf. “Aha,” I thought.

Excited by the prospect of trying something new, I made a hot mug of home-grown peppermint tea, with a generous spoonful of honey, and proceeded to break open the seed pod. Inside was about a half cup of small flat seeds similar to poppy seeds. I chewed up several mouthfuls, washing them down with tea.

“Doesn’t taste too bad,” I thought as I finished the last of the seeds and sat back with anticipation to wait for the Datura to take effect

It didn’t take long. With unexpected force, wave after wave of body rushes enveloped me, similar to LSD coming on, but way stronger — huge waves of energy that made every hair on my body stand on end.

I noticed that the mug I was drinking tea from was becoming unusually heavy. It was a large hand-made ceramic piece, somewhat weighty, but nothing like this. It felt like it weighed about thirty pounds. In fact, everything, my body included, was getting very, very heavy — as if on the planet Jupiter, with way more gravity than what we’re used to here on earth.

“This is too much,” I thought, as I sank to the floor under my own weight, “I’ve got to get rid of it.”

I crawled on my belly out the front door into the morning sunlight and stuck two fingers down my throat as far as they would go, hoping to vomit up what I’d swallowed. I gagged a few times but nothing would come up.

Resigned, I crawled back inside. “I can handle this,” I told myself bravely, “I’m a Yogi.”

Taking big doses of LSD had taught me to let the ego die, relax into the fear, and go out the other side to a place where nothing could touch me because I‘d given myself up completely.

As I always did before yoga practice, I slipped out of my clothes, only this time I did it while lying flat on the floor like a snake shedding it’s skin. I grabbed the thick canvas gym mat with a red four-peddled lotus chakra I’d painted on it and rolled it out into the center of the room where the old floor curved gradually up to a slight peak.

I crawled onto the mat, folded my legs into the full lotus, straightened my back, and gazed over at the undulating silky white curtain that separated the main room from my small kitchen. It was a relief to be back on my usual meditation spot. The repressive feeling of excessive weight dissipated.

I don’t remember much after that, except that I know I wasn’t passed out or unconscious. I spent the entire day sitting there, tripping wildly, hallucinating like crazy, leaving my body and showing up in different places. It was jumbled and chaotic, one disconnected episode after another, with memory blackouts in between.

I was to learn later that sitting in the full lotus with legs locked so that the body can’t get up and run around while the mind is tripping elsewhere, was apparently a good thing to do and might have even saved my life, or at least spared me major embarrassment. Like Mel’s field trip students who fell into the Colorado River, people on Datura (or Jimson weed as it’s called in the Southwest) frequently run off cliffs or onto busy highways.

When I finally stood up the sun was going down. I’d been sitting in the full-lotus the whole day — way more than what I was used to (datura was once used as an analgesic for bone setting and surgery).

The drug had apparently worn off enough for my memory to start functioning again.

The next thing I knew I was in Berkeley, walking up the sidewalk past Live Oak Park towards my parents house, as I’d done numerous times. Everything seemed normal. I completely forgot I was on Datura. I went up the steps and rang the doorbell. No one answered. The front door was unlocked, so I went in.

As I often did when visiting my folks, I walked through the house to the kitchen, opened the refrigerator and peered inside to see if there was anything good to eat. Sure enough, a big, beautiful red apple beckoned from one of the shelves. I reached for it and in an instant I was back in the foothills, my bare legs painfully tangled up in a barbwire fence on the hill overlooking the few buildings that made up the town of Copperopolis.

Somehow I managed to extricate myself from the barbwire and stumble back down the slope in the dark. I was grateful I’d returned to my body before I got to the highway — where I probably would have run naked through the town, whose residents were already skeptical of me.

I realized later that without my awareness my body had walked up a hill that was about the same slope and distance as walking up the sidewalk to my parents house, which apparently was a mental projection in a duplicate body, a parallel hallucination that had seemed perfectly real, even ordinary, with nothing out of place or unusual. The pain from the barbed wire must have provoked an abrupt return to my original body.

Once I was back in my room again I lit the kerosene lamp — only to discover I was bleeding profusely from deep gashes across the top of both thighs from the barbed wire. I didn’t even have a Band-Aid and this looked like it would require some stitches.

I did the first thing that came to mind. I visualized myself drawing light energy from my solar plexus into both hands and then I glided my open hands above my thighs while directing the light down into the wounds. It was a healing ritual I’d come up with and practiced on many an ailment, but never with such success — the bloody slashes closed up and disappeared, leaving behind a clean white scar across each thigh.

I’d write it off as an hallucination, except for the fact that both scars, several inches long, are still visible over fifty years later. A little memento from the Datura Lady.

I’d barely had time to compose myself, when headlights shone through the window and I heard a car coming down the hill. I looked out the window. Sure enough, a small Hillman coupe was pulling up outside. It didn’t occur to me that there was no longer a road to my place and I hadn’t had a visitor in over a year.

“What a time for someone to show up,” I thought, “When I’m totally out of my mind on some exotic drug.”

I peered through the window under the curtain as three people got out of the car. A younger man who was the driver walked around the pond and disappeared into the woods. An old man with a white beard went and sat down near the edge of the pond and gazed into the water. The third person, a woman, came in my back door, through the kitchen, and walked into my room.

That’s when I remembered I was still totally naked. I grabbed my pants but every time I tried to get my legs into them I fell over backwards like I was drunk. After several clumsy attempts I laughed sheepishly and stood up to confront my visitor.

She was a stout, nondescript middle-aged woman with dark hair, possibly Hispanic or Italian, quite unremarkable — like somebody’s mom. As I looked at her she suddenly changed into a life-sized color photograph on a cardboard cutout, such as might grace the aisle of a grocery store next to a stack of canned beans. I blinked, and she changed back into what appeared to be a real, normal looking person.

I tried to say something, to explain or apologize for my lack of clothing, but my words came out garbled and high-pitched like a raccoon, as if I’d just inhaled helium.

I finally gave up trying to talk when I realized that my visitor was speaking with her mind, the words appearing directly in my head as if I were thinking them myself. She said she was the plant I’d eaten earlier and explained in great detail who she was, who I was, how it all worked. She revealed the profoundest secrets of existence, what seekers like myself long to realize — everything.

Unfortunately I forgot most of it immediately.

One thing I did remember is that near the end she said something to the effect that every person was like a drop of water and that each of those drops eventually flowed into a little stream. The streams flowed together until they became a river and all the rivers eventually flowed into the ocean, which was one huge, all-encompassing being.

She said that she was like a mighty river. With that she changed into a different person, then another and another, both male and female, each one distinctly real and unique. Countless faces one after another continued to appear and disappear — even after I realized I was lying on my bed fading into a deep sleep.

I awoke the next morning and sat bolt upright. Was I still on Datura? I cautiously got out of bed. Everything seemed like it was back to normal. I opened the front door and stepped out into the sunlight. For a moment it looked like any other summer morning in the foothills, when suddenly, in a flash, the entire scene turned red, like a red filter had been placed over both of my eyes. I gasped, turned, ran back inside, got back into bed, closed my eyes and tried to relax.

After awhile I ventured out again. This time the colors were normal, but my relief was short-lived — I realized I’d become incredibly farsighted. Picking up a matchbook I couldn’t read any of the words on its front cover until I’d placed it on the ground about ten feet away from me. I could see a car going up a ridge several miles away in almost perfect detail, even the people inside, along a road I’d not been able to see at all before.

“Shit, what have I done?” I thought, almost laughing to myself, “I’m an artist. I depend on my eyes. I’ll have to get special brushes ten feet long,”

As the day wore on I was relieved to see that I was getting less farsighted each time I placed the matchbook cover on the ground in front of me. By nightfall my vision was back to normal. Later, when I went to the Optometry Department at the University of California in Berkeley and had my eyes tested, they were perfect, even better than they had been before.

Afterward

It was interesting to read Carlos Castaneda’s book, The Teachings of Don Juan a few years later. He warns against ingesting any part of the plant because she can easily kill you. In the book a paste made from Datura root is spread on Castaneda’s legs that causes him to fly and have various hallucinations. Strange, very real-looking people, who appear out of nowhere, also figure predominantly in his books, but not connected directly with Datura — while that’s the only time I’ve seen such beings.

After taking Datura I realized that LSD, Psilocybin mushrooms and Peyote or Mescaline, are in an entirely different class when it comes to Hallucinations. Those drugs merely alter the perception of the immediate surroundings but are unlikely to create completely separate experiences of being somewhere else or of seeing people who did not exist before ingesting the drug. That’s what was so remarkable about Datura — each event and the people who appear are ordinary and real, rather than ephemeral or distorted, but they are still total hallucinations, or at least not a normal part of this reality.

Unfortunately the experience of Datura is so disconnected and disorienting that it is both unpleasant and without much benefit (for me at least) in the way of insights or transcendent experiences, such as psychedelics can sometimes reveal. The one thing I did learn from Datura is that the mind can create an entire reality out of thin air. We are dependent upon our senses for a perception of reality. That’s all we know. When we meet someone or find ourselves in a particular physical location, we assume it’s real. Datura showed me everything might instead be “only mind.”

Please be advised (from Wikipedia) — if you’re thinking of trying Datura, don’t. The tropane alkaloids responsible for both the medicinal and hallucinogenic properties are fatally toxic in only slightly higher amounts than the medicinal dosage, and careless use often results in hospitalizations and deaths. The amount of toxins varies widely from plant to plant. As much as a 5:1 variation can be found between plants, and a given plant’s toxicity depends on its age, where it is growing, and the local weather conditions. Additionally, within a given datura plant, toxin concentration varies by part and even from leaf to leaf. In traditional cultures a great deal of experience with and detailed knowledge of datura was critical to minimize harm.

THE CITY OF TEN THOUSAND BUDDHAS

When we first moved to Mendocino County on the north coast of California I worked as the director of a the Mendocino Art Center. During one of my forays inland to the county seat of Ukiah to get supplies for an art reception I took a wrong turn — which led straight into Talmage, a tiny suburb of the city. The road ended at an auspicious arc of a gate that loudly proclaimed “City of Ten Thousand Buddhas.”

When we first moved to Mendocino County on the north coast of California I worked as the director of a the Mendocino Art Center. During one of my forays inland to the county seat of Ukiah to get supplies for an art reception I took a wrong turn — which led straight into Talmage, a tiny suburb of the city. The road ended at an auspicious arc of a gate that loudly proclaimed “City of Ten Thousand Buddhas.”

I’d heard that a Chinese zen master from San Francisco, Hsuan Hua and his followers, had bought the old Mendocino State Asylum for the Insane and were transforming it into a Buddhist Monastery.

Sensing that fate was somehow at work I drove right on through the gate and parked in front of what appeared to be the office. I walked inside and asked the young Chinese fellow behind the counter if there was a schedule for zazen (meditation). He didn’t speak English, and I don’t know a word of Chinese, but after some pantomime he suddenly grasped what I was referring to and excitedly pointed down a street and almost shouted “Tathagata, Tathagata.”

The narrow streets were all marked by faux street signs with names like “Proper Work Avenue” and “Wisdom Way.” I finally found “Tathagata Boulevard,” which led to “Tathagata Hall,” an old, weathered, unpainted grey stucco building with protruding roof tiles that gave it an oriental character.

It was an overcast winter day and the leafless trees and stark bare courtyard created a mood that was strangely beautiful and silent. I imagined I was a traveling monk who had just arrived at an ancient Chinese monastery.

When no one answered my tentative knock on the door I opened it and walked slowly down a long musty corridor lined with empty cells behind steel bars, which I would learn had formally housed deranged mass-murderers and the most dangerous of the state’s criminally insane. Without much remodeling the tiny solitary cells had become home to severely ascetic Buddhist monks of the Chinese “Chan” tradition.

The misty light cast a spell over me as I wandered through the deserted old asylum. I’m fascinated by ancient buildings and long-abandoned sites of intense human activity, which, although desolate and empty, can still harbor subtle lingering impressions of their former inhabitants,

A large restroom along the hallway appeared to have been completely unchanged from former times. The old round fixtures, heavy porcelain sinks and urinals, replete with ancient odors and stains, were profoundly weighty and substantial

A large restroom along the hallway appeared to have been completely unchanged from former times. The old round fixtures, heavy porcelain sinks and urinals, replete with ancient odors and stains, were profoundly weighty and substantial

Built with the sturdy materials and workmanship of an earlier time, everything in the old structure, from high ceilings to yellowing walls and dark wood, was weathered and worn by the passing of a multitude of insane asylum inmates — whose ghostly tormented souls seemed to float in and out of the corners of my mind like peripheral visions.

Finally I stumbled into the meditation hall, a long narrow room with an extremely high ceiling and skylights from which rays of light drifted down. Meditating monks lined both sides of the room facing one another across a wooden floor — all of them were Chinese except for one Caucasian, who came to my rescue and escorted me to a sitting cushion near the door.

I quickly settled into the palpable stillness that pervaded the room. I noticed that the monks had old pink or blue pastel blankets over their legs or around their shoulders that looked to be holdovers from the insane asylum days. Many of them were nodding and falling asleep. I learned later that this was the final part of their annual three week retreat during which they rose at 2:30 in the morning after only a few hours of sleep, usually taken sitting up in the full lotus. They are encouraged to undertake austere vows such as never to lay down. A few of them walked from the Mexican boarder to Canada while executing a full prostration with every third step, emulating their master who had crossed all of China in the same manner.

There was no bowing, chanting or other ritual in the meditation hall that afternoon. Between silent sittings we walked at a brisk pace around the room several times. For awhile a slender old monk in faded robes stood on a platform at the front of the room and gave a solemn talk in Chinese. Since I didn’t understand what he was saying, I concentrated on his non-verbal communication — an exercise I find most interesting.

When it began to get dark I felt duty calling me to finish my errands for the Art Center. After bowing to my motionless and unresponsive hosts I slowly walked back to my car, savoring the moment and the lingering, euphoric calm engendered by repeated periods of zazen. I resolved to return the following year and attend all of their next annual retreat, during the holidays in December and January, but I never did.

I’ve heard they’ve spruced up the buildings and grounds considerably since then, including opening a vegetarian restaurant. The large campus serves and is supported by the Chinese lay community in San Francisco. It’s said there really are ten thousand statues of the Buddha there and many colorful rituals and ceremonies are conducted.

I suspect the monks in the recesses of the Tathagata Hall are only a small, but essential part of what goes on there.

BLANCHE HARTMAN

Senior Dharma Teacher Zenkei Blanche Hartman served as an abbess at San Francisco Zen Center — one of the first women to lead a Zen training temple outside of Asia. When she died in 2016 at the age of 90 I wrote a short remembrance of my encounter with her a few years earlier.

Senior Dharma Teacher Zenkei Blanche Hartman served as an abbess at San Francisco Zen Center — one of the first women to lead a Zen training temple outside of Asia. When she died in 2016 at the age of 90 I wrote a short remembrance of my encounter with her a few years earlier.

I had decided to take advantage of the Zen Center’s generous open-ended offer for anyone to do dokusan with a teacher at their City Center. Since Blanche Hartman was the only one there older than myself and I’d never actually met her face to face, I signed up for an interview with her.

Because our meeting was during the center’s 5:30 morning zazen (meditation) I drove down to Berkeley the day before and stayed at my brother’s overnight.

With the first morning light I crossed the Bay Bridge to the Zen Center in the lower Haight, a lovely old brick building designed by Julia Morgan for a Jewish women’s home, with a large ballroom in the basement — an ideal space for a Zendo (meditation hall).

I went up the steps and knocked on the massive door. A young woman in black robes answered and directed me to a small room on the corner of the top floor. After the ritual bell ringing and bows I folded myself into the half lotus and sat facing Blanche Hartman a foot or two in front of me.

She was an impressive figure. Even in her eighties she sat ramrod straight in perfect meditation posture, brown robes precisely arranged and her gaze direct and relaxed.

“This time is for you,” she said.

After a few minutes of silence we launched into an animated discussion. She more than held up her end of it, with stories of friends and Zen Center episodes from the past. When two people are one in their innermost heart, even though they meet for the first time, it’s like old friends getting together.

When she said that what made Suzuki Roshi so special was his ability to see the Buddha Mind in everyone I nodded in earnest agreement. She also described how Richard Baker, the disgraced successor to Suzuki, was a marvelously talented teacher with a unique ability to bring out the truth of zen in personal encounters.

I related one of my favorite metaphors for meditation. When I was a kid my parents used to take me to Playland by the Beach in San Francisco. In the funhouse, past the wonderful life-size wooden figure of the fat lady rocking back and forth in gales of laughter, there was a huge round hardwood wheel mounted on the floor, surrounded by low padded walls. At the sound of a bell everyone entered and scrambled to sit down on the big wheel, cramming together with backs towards the center. At the sound of another bell the wheel started to slowly turn. As it picked up speed people on the outer edges of the crowd started to slide off, flying into the padded walls. Finally, as the wheel was turning faster, only one person, who had managed to find the exact center, was left spinning there. Eventually even they could not maintain a perfect balance and were pulled off by centrifugal force.

“That’s samadhi!” Blanche exclaimed.

Since we were both quite old, we also talked of death at length. I told her of my parents who had both died recently in their nineties, within a few hours of each other.

Blanche said that she was with a close friend who had suddenly put her hand to her head and complained of a sharp pain there. “A couple weeks later she died of a brain tumor. Just like that,” Blanche said, snapping her fingers.

We must have rambled on for an hour before she suddenly remembered there were others waiting to see her. We quickly bowed and I went out the way I’d come.

When I got back to Berkeley, I lay down for a brief nap. Soft light streaming in through a lace curtain on a tall window triggered something deep within me, one of those sublime “moments” that I think anyone who loves meditation occasionally experiences.

It felt like a continuation of my meeting with Blanche Hartman.