“The way to gain power, is to save power.”

Ta Hui

A significant amount of research is accumulating that documents an impressive array of positive effects from meditation. However, such physical and mental benefits are only side effects. It’s unlikely that taking up meditation to lengthen telomeres and live longer, or the many other benefits researchers have discovered, is sufficient to provide the degree of motivation needed to continue the practice over the long haul.

The real benefit of meditation is intangible, even spiritual or religious — except that it doesn’t require any particular set of beliefs. It can, with a little tweaking, fit into just about any belief (or no belief) system because it goes directly to the source of all religion. Thus it has been called true religion. It appeals most to those with a sincere desire to know what this life is, who we are, and where we come from.

Meditation can also be completely secular and non-theistic, which is one reason it has become popular with some scientists and psychologists. It employs an openness and a clarity of observation that is similar to the scientific method. But instead of only observing external phenomena, meditation also entails self-observation of internal phenomena.

Despite all the recent attention meditation has received, the general public in the West is still largely unaware of the refined meditation technologies and the vast body of literature, dating back to prehistory, that developed in the East, particularly in India, China and Tibet.

This won’t be an attempt to present a comprehensive overview of all the various meditation practices. Instead it is just some of what I’ve learned from my own experience of a lifetime of dedicated practice and study, primarily in the Zen school of Buddhism.

POSTURE

Meditation can be reduced to one sentence — just sit in the correct posture until you remember who you are.

While the essence of meditation is not in any particular posture, good posture makes it easier to concentrate on what is immediately present. I often hear people say that meditation posture is not important, that they meditate lying down in bed or on the couch. I meditate in bed and on the couch too, but I also meditate in the prescribed posture, and it simply works better. It develops an inner strength that makes meditation in other positions more effective.

Neuroscientists are discovering what yogis have known all along — that what is done with the body can have a remarkable effect on the mind (and vice versa). For instance, research has shown that what we do with our facial muscles, such as smiling, triggers positive responses in our chemistry, even if we’re not actually happy about something. When we’re calm we breath slowly and deeply, and if we’re upset, breathing slowly and deeply has a calming effect. Likewise sitting up straight, rather than slumped or lying down, stimulates physiological responses that produce vigor and awareness.

While it’s easier to relax lying down, learning to relax in a slightly challenging, upright posture is uniquely powerful. The breath, which energizes the whole system, is strongest and most efficient when sitting up straight with good posture.

When aiming for the correct meditation posture the most important point is for the spine to be straight and balanced, in it’s natural upright posture. If you rock forward and back again, you can feel the natural curve of the lower back. Then, pulling the chin in, the chest expands, the lungs open up, and the breath (always through the nose) slows down and deepens. The crown of the head rises up towards the ceiling as if pulled by an invisible rope. When the shoulders and arms are relaxed downwards, and the hands rest lightly on the lap or upper foot, the arms make a large flat circle around the torso.

The posture doesn’t need to be exaggerated. It should be relaxed and comfortable (once the body/mind adjusts thru daily practice). Checking the posture occasionally during meditation, especially the chin, which tends to drift upward when lost in thought or downward when sleepy, serves to bring one back to the body and the present moment..

THE FULL LOTUS

For most of us, to be able to sit comfortably in the full-lotus, with both legs crossed over the tops of the thighs, takes concerted effort over a considerable period of time. For many it’s impossible.

Fortunately, the basic ingredients of the full lotus are attainable in several other meditation poses.

Whatever pose is taken, the spine should be in its natural, upright position, so that the weight of the body doesn’t pull on muscles and ligaments, but instead rests lightly directly downwards. Rocking forward and from side to side when first assuming the posture balances and centers the body on the spine.

The position should also be stable and firm, which is what the locked legs in the full lotus with both knees firmly on the floor accomplishes.

SITTING IN A CHAIR

I’ve had considerable experience sitting in chairs. It’s not quite as stable and energizing as sitting on the floor in the half or full lotus, but it works as well otherwise, making deeper levels of meditative experience available to almost anyone willing to put in the time and effort.

A firm, arm-less, straight-backed chair is best. A wedge shaped cushion or some pillows to raise the butt up just a little higher than the knees so that the thighs slope down slightly, will naturally result in good posture when the chin is pulled in.

It’s often recommended to sit with the back not resting against anything. However, I’ve found that when I’m sitting on a chair without a back support I tend to fidget and have more trouble settling down, while a small pillow against the low back increases the feeling of stability and calm.

Sitting in a chair, the posture can still be upright, with the chin in, the spine naturally balanced, and the shoulders relaxed downward. Instead of the knees, both feet should rest firmly on the floor.

Sitting upright on a chair, with the hands resting downwards on the thighs is the ancient Egyptian posture for meditation.

HALF LOTUS

Sitting in the half-lotus (with only one leg on top of the other) or quarter-lotus, and even with one foot in front of the the other (Burmese posture), are stable, energizing poses — just as long as both knees are on the floor. Even seasoned meditators are likely to use the half-lotus for long retreats. Alternating which leg is on top with each meditation period is a good preparation for the full lotus, while taking pressure off the knees and balancing the body.

The best way to get the knees accustomed to sitting in the half or full lotus is to sit that way repeatedly — gradually and patiently extending the duration. My experience is that sitting crossed-legged on the floor is actually good for the knees. What’s dangerous is to get into it too abruptly, rather than gradually. Likewise, forcing a leg into position could cause injury.

Some pain and numbness in the lower legs and feet is normal for many people when first sitting crosslegged on the floor — just don’t try to stand up while still numb. It should disappear in a few minutes after unfolding the legs. Knee pain that persists very long after getting up is a sign to back off in order to avoid injury. Getting the body accustomed to sitting on the floor can take quite a while and require considerable persistence. Be gentle and patient.

For sitting on the floor, a “zafu,” (a round meditation pillow stuffed with kapok) is usually necessary, along with a “zabuton” (a large flat pad filled with cotton batting) underneath. I’ve used a tightly folded-up blanket for a zafu on top of a rectangular sleeping bag folded in half. The point is to raise the butt up enough so that the knees can rest comfortably on the floor, which should be padded.

Getting both knees solidly on the floor creates a tripod-like triangle that is very stable and supportive of an upright spine. At the end of this article is a hatha yoga exercise to open up the hips and knees in preparation for sitting in the full or half lotus.

EASY POSE

The “easy pose” with the lower legs loosely crossed in front of the body, and knees sticking up in the air, is unstable and not recommended. It encourages the body to curl forwards, putting pressure on the low back and the muscles that support the spine.

However, the easy pose can serve as a transition to a more stable pose, providing one sits on a zafu to raise the butt up. Then the knees can gradually be lowered towards the floor (padded) to eventually sit in the Burmese posture with both knees on the floor, legs spread wide and one foot in front of the other on the floor. With time and patience one can also gradually transition to the quarter and the half lotus.

A friend in his seventies started out meditating in the easy pose, and gradually went to the quarter lotus and was finally able, after a year, to sit comfortably in the half lotus.

THE KNEELING POSE

The kneeling position, or Japanese “seiza,” is a good, stable posture, which many people find easiest, and even quite comfortable for long retreats. Traditionally, in zen meditation halls (zendo) there are no chairs, and everyone has to sit on the floor. The seiza position is a good option for those who find sitting cross-legged too difficult.

In order to sit comfortably kneeling for long periods the butt must be raised up off the backs of the feet. A zafu set on its side between the feet can be used, but eventually most seiza sitters prefer to use a special little “meditation bench” the right size and angle to support a firm posture.

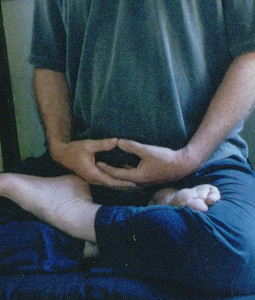

HAND POSITION

The hands, like the rest of the body, should be set into position and held for the duration of the sitting.

I employ the “cosmic mudra,” with the back of the left hand resting on the right palm and thumbs barely touching to form a small circle just below the navel. At first it feels awkward, but when it becomes familiar, it reflects the general level of relaxation in the entire body.

An easier hand position to hold is with the back of the right hand resting against the left palm, with the left thumb held in the palm of the right hand by the right thumb.

Placing the hands on the knees is also fine. Sitting in the full lotus, the hands resting on the knees, arms straight to form a triangle, with palms facing up and the tips of the thumbs and forefingers lightly touching, is a classic yoga pose.

OPEN YOUR EYES

Meditate with the eyes open. It’s often said that this is to prevent falling asleep, or daydreaming and visions, which might be more likely with the eyes closed.

I think there’s more to it than that.

With the eyes open and relaxed, not focused on anything in particular, we see the surrounding space as if in a round mirror. This helps clear the mind of nagging thoughts and internal noise, and makes it easier to go into Samadhi, the clear, global awareness that leads to insight.

The eyes may also be “fixed” on a small spot, usually about three feet away and slightly downward. This tethers attention and develops concentration. For years I meditated every morning and evening with eyes fixed on a small shiny object on a dark wooden wall.

Looking straight ahead, with “spread out” vision, seeing both sides of the visual field at once, while more difficult, has a unique effect, and is used in many advanced Tibetan practices.

In yoga, especially when doing pranayama breathing exercises, it is often recommended to look at the tip of the nose, or simply “down” the nose. It takes a little practice, but it is physically very powerful when one can relax into that view.

Zen, and most other Mahayana and yogic sects, meditate with eyes open. It makes it easier to avoid visual illusions, to stay present and awake, to transition to ordinary activities, and to realize oneness of subject and object (samadhi).

Eyes closed is good for body scans and progressive relaxation, but those can also be done with eyes open. Even visualizations are surprisingly easy with the eyes naturally open and relaxed. When I experimented with shamanistic journeying I was able to get into self-propelled visions while sitting in meditation with eyes open, without drumming or other assistance.

In some traditions they face a wall a few feet away, but with practice it’s possible to face almost any scene without getting drawn into it. I usually face out into the room and look slightly downward towards the floor about three or four feet away, through “soft,” half open, unfocused eyes.

Most people think meditators always sit with their eyes closed. On family vacations I liked taking the kids to the swimming pool. I’d place my meditation pillow on a folded towel in a discreet location with a good view of the pool and sit and meditate while watching the children play in the water. When I mentioned what I was doing, my sister-in-law became concerned that I wasn’t really watching the kids. “That’s the only thing I was doing,” I explained, “unlike most of the other parents around the pool who were yakking or reading.”

WHEN TO MEDITATE

Sitting Meditation can be practiced anytime it is convenient, but for most of us, the first thing in the morning is best. At that time our stomachs are still empty and (hopefully) the concerns of the day have not yet engulfed us. Sitting in meditation, breathing deeply and letting go of rumination on the past and future, even if for just a few minutes, gets the day off to a great start.

Other good times are before meals and the last thing before getting into bed at night. Meditating at the same time every day and linking it up to other routines, makes it easier to develop a comfortable habit of meditation. Regular, consistent daily practice opens up the opportunity to experience spontaneous moments of intuitive insight, that can happen anytime, on or off the meditation cushion. As Kobun, a zen teacher I trained with, liked to say, “Enlightenment is an accident, and zazen (meditation) makes you accident prone.”

A good way to establish a meditation habit is to make a vow to sit down on your meditation spot the first thing out of bed in the morning and the last thing before getting into bed at night. The amount of time is less important than just getting into position consistently. Some days you might only sit for a minute or two. Other days you’ll get into it for longer. Eventually you can set a minimum time (20 to 30 minutes is very good), but what’s most important is to get into the habit of doing it at the same times, in the same place and in the same posture, every day, even if only 5 or 10 minutes. It’s said that it takes 2 months of consistent practice to establish a habit.

If you can’t sleep at night, try meditating. As I’ve gotten older I often wake up in the middle of the night and can’t get back to sleep. It’s a wonderful time to meditate — there’s not much else to do, and it’s usually very quiet. So I force myself to get up out of bed and sit until I’m feeling relaxed and sleepy. If I’ve been meditating enough, I can quiet my mind and relax my body sufficiently to fall asleep almost anywhere, anytime.

I know people who only meditate with a group or when on retreat. That’s probably better than no meditation at all, but it’s not nearly as effective as consistent daily practice. Unless you plan to spend your entire life living in a practice community or monastery, if you’re really serious about meditation, I urge to you make the effort necessary to establish a personal, daily practice.

HOW LONG?

I frequently used to decide I’d start getting up really early in order to meditate for a longer time. It always seemed like a great idea the night before, but I’d find myself in an entirely different frame of mind when the alarm would go off in the frigid dark before dawn.

Attempting too much at first is a common mistake.

Meditation should be natural and enjoyable, so that instead of wasting energy in a vain struggle we can apply ourselves wholly to the matter at hand. It’s better to meditate only ten minutes consistently every morning than to attempt more than is comfortable and give up before having even made a beginning.

A timer can eliminate the need to look at a clock. The length of time can be gradually increased once meditation has become a habit.

It’s important to establish a meditation schedule and stick to it religiously. If you only meditate when you’re inspired to do so, you’re likely to end up meditating very little, or quitting once the novelty wears off.

For decades I meditated twice a day, first thing in the morning and last thing at night, for the length of time it took an incense stick to burn down (about half an hour).

In some Tibetan traditions they meditate for short periods throughout the day. This can fit nicely into work situations, where regular breaks are recommended to refresh body and mind. A short meditation is especially beneficial at such times. It’s said that after awhile the numerous little meditations merge with other activities into one continuous meditation.

NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF MEDITATION

Meditation is very powerful and like any powerful practice it can be dangerous. Research shows that about 10% of people who take up meditation have adverse effects. Meditation makes changes to the brain that can affect a few people negatively and take years to recover from. Work into it gradually and carefully. If you notice adverse effects such as anxiety or insomnia, either change the practice, or stop it entirely until you feel better. A meditation teacher might tell you to just work through it, but everyone is different and even the most experienced teacher hasn’t seen all the possible outcomes.

Apparently there’s a correlation between how much time one spends in meditation and negative effects. An hour or less a day is unlikely to to cause any problems in most people. But some folks start right out with a 10 day vipassana retreat or a week-long zen sesshin. That’s risky and for a few people it can cause serious problems.

As one progresses on the path of mediation it’s natural to increase the amount of time spent in meditation. Over the years I’ve sat numerous sesshin (multi-day intensives) and I usually meditate a couple hours a day and all day every Sunday — with only positive effects.

For most of us meditation is beneficial but it’s not for everyone and it’s not a cure-all.

WALKING MEDITATION

When I first started meditating seriously I was inspired by the Buddha’s legendary vow to not move from his spot under the protective cover of a fig tree until he realized enlightenment. I’d get into the full lotus, grit my teeth, and force myself to remain still, despite increasing discomfort. Eventually I’d remember there was something more important to do — like cleaning the oven.

It was a great relief to finally discover that it was okay to alternate periods of sitting with walking, while still remaining on the same general spot.

Sitting too long without getting up is unhealthy. Alternating sitting and walking allows one to meditate longer. The meditation method being practiced, such as following the breath, can be continued during a period of easy walking.

When practicing walking meditation the hands are usually held against the solar plexus, with the elbows out and forearms parallel to the floor, with eyes lowered.

I like to sit for 25 minutes and walk for 5 minutes, which fits nicely into hourly segments, as well as being easy on the body. Walking in a circle clockwise around the meditation area is traditional, as is back and forth on the same pathway.

Some Theravada Buddhist monks sit for one hour and walk for one hour, for half of each day, year round.

Walking at a normal pace is most popular, although some traditions even walk at a brisk pace. The most meditative method is to walk really slow, with an in-breath upon lifting a foot slightly and an out-breath when placing it half a step forward — which also works well when the space is limited.

Alternating sitting with walking around the same short, easy path, over and over again, it’s possible to meditate almost indefinitely. Seven day zen sesshin retreats consist of 8 to 12 hours of sitting and walking meditation a day, with gung-ho participants continuing to practice through the night.

WHERE

Once we are proficient in meditation it can be done almost anywhere, but at first it’s best to sit in the same place consistently.

In some traditions, such as Thai Forest Buddhism, meditation huts, or “Kuti,” are set in isolated spots for solo practice. I built myself a small hut/teahouse, that currently sits in a secluded area nearby, but can be disassembled and moved if need be.

Meditation can also be practiced outside when the weather is nice. Near the base of a tree or on the banks of a stream are good places, as the ground naturally slopes down, making a meditation pillow unnecessary.

I especially like to discretely meditate while on an airplane or bus. Something about the external movement makes it easier to find that stillness within.

ALTARS

My meditation hut has a simple alcove with a bamboo vase in which I keep fresh flowers. Flowers improve the whole feeling and mood. I also have a small bowl of sand for incense sticks on one side and an antique bell on the other, which I ring to begin and end meditation periods when other folks are sitting with me.

Some practitioners get very creative and include various offerings, pictures of teachers and loved ones, or other items with personal meanings. If one has particular religious beliefs they can be expressed in the altar.

An altar is not necessary but it can support one’s practice and serve to promote a peaceful and devotional environment.

GETTING BACK INTO THE BODY

Some people like to talk about “out-of-the-body experiences,” as if they were actually “in” their bodies the rest of the time. In reality, most of us spend far more time adrift in mental activity, such as inner dialogues and story lines, than fully inhabiting our bodies and senses. With all the new information technology the mental clutter has increased exponentially.

Returning to the body is returning to the present moment. Tripping out in repetitive, linear patterns of thought, only takes one further away from this present reality and is not conducive to inner equilibrium and peace, much less enlightenment and liberation.

A simple method for staying in the body, is to pay attention to physical sensations, or how it “feels” at the moment. This is the technique used in Burmese Buddhist meditation to calm the tendency towards discursive mental activity (monkey mind).

Sitting upright in a slightly challenging meditation posture also serves to keep one in the body and the immediate situation. Periodically checking the posture and overall relaxation of the body returns the mind to the present. Likewise, devoting bare attention to the view through half-closed eyes grounds the mind in the moment.

In Soto Zen the word “just” is employed — as in just eating, just walking, just sitting, and so forth. A lot of us are so overstimulated mentally that to “just” eat lunch, without doing something else, like reading or talking, has become very difficult and boring.

To “just sit” looks simple and easy, but proves to be quite challenging in practice.

MEDITATION AS MEDICINE

Like some medicines, meditation doesn’t always taste good going down. It can be difficult and boring, even painful. But like medicine, if you just take it everyday as directed, it goes to work in you without your being aware of it, until eventually you’re healed without having to think about it. This is an important point.

If you find yourself unmotivated and resistant to meditation, even though you want to practice, it’s likely because you are overthinking it, trying to fit it into some scenario or expectation of how you think it should be, rather than having faith in it and letting it be what it is at that particular time.

While simply staying open and present with whatever occurs is the ultimate meditation, sometimes, especially at the beginning of meditation or when resistance sets in, it’s better to “do” something concrete. This is meditation with an object as opposed to meditation without an object. An object of meditation gives the mind something to engage with, and is designed to lead into meditation without an object, which is ultimately the clear and open mind of samadhi.

WATCHING THE BREATH

The breath is the most frequently used object of meditation to concentrate and focus the mind. Breathing should always be through the nose, unless some special exercise is involved.

It’s often recommended to breath just with the abdomen, but I think that’s been oversold and a natural, “complete” breath is best, with the abdomen and the chest expanding and contracting in unison. However, if your breathing is shallow and only in the upper chest, then it’s good to become aware of the movement of the abdomen and deeper breathing. There are also yogic breathing exercises that emphasize abdominal breathing.

Some instructions recommend stilling discursive thought through suppressing imperceptible movement of the tongue by pressing it against the roof of the mouth. That might be a holdover from an earlier yogic practice of lengthening the tongue through special exercises until it could curl back down the top of throat to slowly close off the breath — which it’s claimed can induce a state of hibernation where one could be buried for days and survive. Needless to say, it’s not really necessary to accomplish that feat. But it’s also said that in some kinds of very deep meditation the breath almost ceases completely.

In many meditation instructions the breath is to be observed without interfering. However, in my experience, it’s impossible, strictly speaking, to just “observe” the breath without interfering with it. As soon as one applies consciousness to the breath it comes under conscious control and if the breaths are long or short becomes a matter of volition. The conscious and unconscious breath are two very separate systems (thankfully), so that the lungs continue (normally) to operate quite well without consciously having to remember to breath.

This deep connection with the mind makes the breath as an object of meditation especially useful in relaxing and clearing the mind. Constantly bringing the attention back to the breath is a good way to reign in mental wandering and excitement. This has been compared to tending an ox. When the ox wanders off, a gentle tug on the rope that’s connected to its nose-ring brings it right back. When we notice our mind wandering off we can pull it back by returning the attention to the breath going in and out of the nose.

COUNTING THE BREATHS

An effective way to calm and focus the mind is to silently count the breaths as they come in and out. Counting breaths is a preliminary practice that is especially good for beginners, who are likely to feel overwhelmed by an unending torrent of mental activity when they first begin to observe what actually goes on in their minds during meditation. That, and the frustration that often accompanies such observation, can be alleviated when the task of counting the breath is undertaken.

Doing nothing turns out to be more difficult than imagined. Breath counting gives one something tangible to do, while developing power of concentration.

The easiest way to count the breath is to silently say “one” on the inbreath and “two” on the outbreath, “three” on the inbreath and “four” on the outbreath (odd in, even out), and on up to the count of “ten” on the out-breath, and then start over at one again. This will calm and focus the mind early in any sitting, and is very useful, even for experienced meditators.

At first this is not so easy. Thoughts intrude and one loses track or ends up counting way past ten. That’s normal. The attention should just be pulled back to the breath, starting over at one again.

LENGTHENING THE OUTBREATH

Lengthening the outbreath activates the parasympathetic nervous system, which in turn calms and relaxes all of the physiological systems, including the brain and mental activity.

Extending and letting go into the outbreath makes breath counting even more effective.

Some traditions count only on the outbreath while counting to ten, which works especially well with an extended outbreath. Silently counting just on the inbreath is somewhat more difficult, but in both methods the outbreath can be lengthened, without forcing or exertion, by relaxing into it and letting go of everything else.

When counting only on the inbreath, the extended outbreath can be combined with a word or a “hua tou” (koan key word) like “mu,” or “who?” (as in who hears, who sees, or who am I?) silently spoken. A single, simple word, combined with a prolonged outbreath, serves to turn the mind back on itself, bringing it into the present situation. Like a stone dropped into a still pool, it will send out ripples of insight. It’s a simple method, but it should not be underestimated.

“Om” is another word that combines easily with an extended outbreath and has traditionally been employed, especially in India. Other words can also be used, but they should be simple to say and resonate peacefully within.

Whether using a word with the outbreath or silently relaxing into it, the counting can be dispensed with once the mind is sufficiently concentrated. Counting can begin to feel coarse, or become too automatic after a while. Then simply “following” the breath, and extending the outbreath, will continue to calm and settle mind and body.

I especially like combining attention on the breath with attention to the light coming in through half-closed eyes. Something about concentration on two things at once serves to calm mental and physical activity and induce samadhi (oneness of subject and object).

Once the mind is sufficiently quiet and stable, attention on the breath can be abandoned, along with thoughts and sensations as they arise. Then one can transition to “shikantaza,” just sitting with open awareness, which will naturally stimulate spontaneous moments of deep insight that can happen anytime, on or off the meditation cushion.

Finally, when the mind is settled and one-pointed, contemplation and self-inquiry, “turning” the light of the mind back to its source in the present moment, is practiced.

One can go from counting/following the breath, to shikantaza and contemplation/turning, within a single meditation. During times of intensive practice one will often drop right into calm open awareness when first sitting down to meditate.

With daily practice over a long time, the mind is gradually purified — like polishing a gemstone to bring out its inherent shine and beauty.

TRUE MIND

The natural, original condition of the mind is clarity and openness — like empty space. I think that everyone instinctively knows this, but it’s lost under the weight of habitual mental patterns that are acquired over time.

We are actually free to think whatever we want, or not to think anything at all, but instead most of us are at the mercy of reactions and attachments to the impermanent, temporary circumstances of life.

This mind, our true self, is broad and open, like a boundless, empty field, where everything, the entire movie, constantly arises and disappears — or like a clear mirror in which passing images are reflected, without affecting the mirror itself.

Our true mind is unimpeded and effortless. It is beyond dualistic discriminations such as past and future, self and other, inner and outer, existence and nonexistence, transitory and eternal, and so forth. It transcends all of the conceptual models that are used to organize reality and which have come to be accepted as real, rather than recognized for the mental fabrications they are.

This calm, open awareness is “samadhi.” In Patanjali’s Yogic Aphorisms, samadhi is referred to as being “free of all mental modifications.” When mental modifications do arise, they are allowed to go back into clarity and emptiness, without attaching or reacting to them. When all mental activity finally winds down and ceases, even if only momentarily, it can stimulate profound intuitive experiences.

So this inherent, originally clear, true mind, is conducive not only to calmness and concentration, but to realization and enlightenment as well.

THE LAUGH OF ENLIGHTENMENT

A good way to end each meditation is with a long, hearty laugh.

Neuroscientific research has shown that laughter stimulates the secretion of chemicals that have a strong positive effect on mood and health. Surprisingly, laughter is just as effective when it’s completely artificial, without anything funny to provoke it.

Combining laughter with the thought of enlightenment, the ever-present, original, clear, open nature of everything, is even more effective.

PRANAYAMA (BREATH CONTROL)

Traditional yogic breathing exercises can be incorporated into a meditation routine to arouse and focus energy — or simply as aids to relaxing and letting go of physical and mental tension. They are especially effective for calming an overactive mind.

Breath is energy, it’s the fuel that energizes bodily and mental activities. Focusing on the breath one can feel energy moving through the body, and learn to cultivate those feelings and energies for health and well-being.

THE CLEANSING BREATH

Normally most people breath with only about a third of their lungs, or even less. The remainder of the lungs accumulate toxins and other contaminants that eventually degrade the lungs, causing various health problems later on. A vigorous expulsion of the air in the lungs not only cleanses and detoxifies, but also stimulates and de-stresses the entire body/mind system. It is especially recommended for smokers or after exposure to dust or fumes, and for those with lung or breathing problems.

Not only is the cleansing breath a good way to start the day, it is an ideal way to begin each meditation.

Simply breath out slowly and completely through the mouth while bending forward with the hands on the knees or on the floor in front of one’s seat. Tightening or pursing the lips while exhaling puts some additional pressure on the lungs, which opens up the multitude of tiny sacs that are essential to efficient use of the air and revitalization of the body.

Continue to exhale slowly and calmly until it seems that no more air will come out — then blow three short bursts to get every last bit of air expelled. Follow with a deep inhalation through the nose. Or, if one has the genetically inherited ability, breath in through a wet tongue rolled up like a straw, to sooth and heal the lungs with moisture.

To heighten the positive effect of the cleansing breath, imagine all the toxins, both physical and mental, being blown out with the outbreath, along with distracting thoughts and negative emotions — which is essentially what takes place with this simple breathing exercise.

ALTERNATE NOSTRIL BREATHING (NADDI SUDDHI)

The yogic exercise of breathing in through one nostril and out through the other, with the thumb and ring finger to alternatively open and close each side of the nose, is traditionally used to calm the mind and purify the nerves. I think it also synchronizes the two hemispheres of the brain.

Tucking the forefinger (pointer), and the middle finger, into the palm of the right hand, with the ring finger and little finger sticking up, place the right thumb against the side of the right nostril to close it. Breath in through the open left nostril for the count of eight, hold for an instant, then swing the hand so the ring finger presses on the side of the left nostril to close it and the thumb lifts up off the right nostril. Breath out through the open right nostril for the count of sixteen. With the left nostril still closed, breath in for the count of eight through the right nostril. Hold for an instant while closing the right nostril with the thumb and taking the ring finger off the left nostril, then breath out for the count of sixteen through the left nostril. That is one round of alternate breathing. The count can be synchronized with the heartbeat which should become audible with the slower and deeper breathing.

Tucking the forefinger (pointer), and the middle finger, into the palm of the right hand, with the ring finger and little finger sticking up, place the right thumb against the side of the right nostril to close it. Breath in through the open left nostril for the count of eight, hold for an instant, then swing the hand so the ring finger presses on the side of the left nostril to close it and the thumb lifts up off the right nostril. Breath out through the open right nostril for the count of sixteen. With the left nostril still closed, breath in for the count of eight through the right nostril. Hold for an instant while closing the right nostril with the thumb and taking the ring finger off the left nostril, then breath out for the count of sixteen through the left nostril. That is one round of alternate breathing. The count can be synchronized with the heartbeat which should become audible with the slower and deeper breathing.

Alternate breathing can also be done without using the fingers, just the mind, as long as both nostrils are completely clear and open, and one has practiced with the fingers first. I think this has a more powerful calming effect on the brain hemispheres and nerves.

An even more advanced form of alternate breathing, with retention of the breath after each inhalation, necessitates the use of anal and chin locks to force energy into the abdomen. It is said to be dangerous to undertake without a teacher.

THE ORGASM BREATH

This is a softer version of the yogic “bellows breath”, or Bastrika, which I used to call the eraser breath because of its efficacy in clearing the mind of discursive thinking — at least temporarily.

The bellows breath, which is often referred to as the “breath of fire” because of its use in arousing primordial energy, is a sustained period of vigorous, rapid outbreathing (through the nose), using only the abdominal muscles, like a bellows, followed by a deep inbreath and retention of the breath for an extended period, pressing the chin down and back to close off the breath from above, and closing the sphincter while lifting up the perineum to force energy upward.

In the late sixties I was enthusiastically practicing hatha yoga everyday. Also, despite the many warnings that it is dangerous, I was a dedicated devotee of the bellows breath — partly because the hyperventilation made me quite high.

It turned out to be dangerous in an unexpected fashion.

I was frequently doing various breathing exercises or chanting while driving. One day, speeding down a freeway in my old Volvo, I engaged in a vigorous round of Bastrika, or bellows breath, after which I took a deep inhalation and applied the anal and chin “locks” to hold the breath in my navel chakra. The next thing I knew, I was traveling backwards going in the same direction, but along the shoulder of the freeway in a huge cloud of dust, as a family driving past looked on in astonishment. I’d apparently blacked out while my car did a 180 down the freeway.

So, to be safe, don’t attempt any of these exercises while driving.

Now, in my old age, I’ve toned it down a bit. The rapid belly-breathing irritates my lower intestinal tract, so I breath in normally using my chest as well, with both inhalations and exhalations equal — starting slowly, and gradually making the breathing deeper and more rapid, as if leading up to a sexual orgasm (visualization can be applied here if helpful), until finally reaching a crescendo of deep breathing, followed by a huge, full, deep inhalation.

But no retention. Instead, after a slight pause, a long exhalation is let slowly out through the nostrils in a normal manner, resulting in a delicious feeling of release and calm. It has all of the advantages of the billows/eraser/fire breath, without any of the dangers.

DIRECTING AND VISUALIZING THE BREATH

Awareness has no location. It can move around the body and feel different areas and organs at will. When the awareness rides on the energy of the breath, it can be felt going in and out of any part of the body it is directed to. In a popular Taoist exercise to circulate the energy of the breath, the inhalation is brought down the front of the body to the lower abdomen and the exhalation is brought up the back to the crown of the head.

In progressive relaxation, the breath, especially the outbreath, is felt flowing in and out of each part of the body from the head to the feet, relaxing and soothing each region and organ it passes through.

Starting with the jaw, the in and outbreath is felt there, along with a relaxation and letting go of that area — next the ears, then the eyes and the brain are relaxed. Flowing on down and breathing in and out through each part, the neck, shoulders, arms and hands are relaxed, then the upper back and shoulder blades, the chest, heart and lungs along with the vascular system, the stomach and liver, down into the intestines, kidneys and bladder, to the lower back with the bones, spine and skeleton, then the abdominal muscles along with one’s overall musculature, the sex organs with other glands up the spine, the buttocks, thighs, knees and lower legs — all the way to the feet, using the inbreath and an extended outbreath to relax each area in turn.

It’s not necessary to get so anatomical in progressive relaxation. What’s most important is to actually feel the breath and relaxation move in various areas of the body. It’s a great preparation for falling asleep at night while lying in bed, but it’s also very effective for relaxation while sitting in meditation — a technique similar to a “body scan.”

A more advanced method is to visualize and feel warm, soothing butter, an ambrosial nectar, melting and flowing from the top of the head over each part of the body, relaxing and healing as it fills the lower body.

CHANTING

Repetitive chanting of simple prayers or mantras has been used since the dawn of history as a kind of meditation to calm and focus the mind. When done single-mindedly for long periods repetitive chanting can even induce samadhi.

Chants are an individual choice and can depend upon the practitioners beliefs. As with an altar, they are not strictly necessary but they can serve to support one’s practice and direct the mind in beneficial ways.

In zen, chanting of sutras and texts at the beginning of meditation, before meals and at the end of the day, is used as a teaching device and reminder of certain basic principles.

Below are two chants I developed based very loosely on some Mahayana Buddhist chants. I’ve tried to use plural pronouns and make the words declarations or positive statements rather than supplications or appeals. Feel free to improve on them, ignore them, develop your own chants or use some from different traditions.

CHANT TO BEGIN MEDITATION

With a deep inbreath (through the nose) raise both hands and join palms overhead, then gradually lower them down the front of body, while slowly chanting in a deep, resonant voice (or silently) the following three words, each word extending and blending with the next —

Ooommm, aaahh, huunng

With joined palms held at about neck level, chant slowly and evenly —

Taking refuge, in the One Mind, in the One Heart, of this moment.

With all beings, may we always be enlightened.

Ho!

Holy One, welcome, welcome (bow)

Offering up all attachment, all anger, fear, and confusion.

Completely free of self-clinging.

Always remembering how rare this life is, how quickly the body fades and dies.

Blessed with mindfulness and strength to practice.

Ho!

From the heart of the holy One, streams of light flow down, bringing blessings and protection. (can be combined with visualizations and feeling)

Finish with a deep bow.

CHANT TO END MEDITATION

With joined palms held at about neck level, chant slowly and evenly —

The benefit of this practice extends to each thing in all places.

All beings are happy, all beings are peaceful, all beings are blissful.

From our heart, streams of light, perfect love, in all directions (can be combined with visualization and feeling).

Take one long breath, stretching up the hands and joining palms overhead, then slowly lower them down to the front of body while chanting the three final words, each word extending and blending with the next (the final word is sometimes pronounced hum)

Om…aah…hung

Finish with a deep bow.

HATHA YOGA AND THE FULL LOTUS

In the late sixties, at the age of twenty-six, I retreated to an isolated shack beside a pond in the foothills of the Sierras to devote myself to meditation. In order to get my body to sit comfortably in the full lotus, I took up the practice of hatha yoga. Unlike today, with yoga studios almost everywhere, hatha yoga classes were very rare in those days. So I read the few books on the subject that were available and started experimenting with the physical postures on my own. The asana that I found to be the most helpful for getting into a full lotus is the head to knee forward bend or “Janu Sirsasana.”

To do the head to knee pose, sit upright, flat on the floor, with both legs straight out in front of you. Pull one foot back towards your groin, with the bent leg on the floor and the sole of the foot against the inside of the opposite thigh.

Keeping the back straight reach forward over the the extended leg with both hands. Be sure to feel the natural curve of the low back and maintain a straight back while folding the upper body forward. With the inbreath stretch out towards the extended foot to eventually grasp the big toe. On the outbreath relax the torso downwards, the head going towards the knee, with the aim of touching the forehead to the straight knee and the elbows to the floor on either side. Continue stretching and relaxing for several deep in and out breaths before switching sides.

To make the knees more flexible for the full lotus, raise the the bent leg and place the foot over the opposite thigh, as in the half lotus, keeping the knee on the floor. Then fold forward over the straight leg as before, stretching and relaxing with in and out breaths, alternating which leg is on the opposite thigh and which is straight out in front. If the pose is repeated two or three times on both sides, you should find that with each repetition you’re able to bend forward and downwards more easily and the bent leg will become more flexible.

Actually sitting in the half or full lotus, gradually extending the time, is the best way to get the body used to sitting that way, but the head to knee pose is a wonderful way to loosen up the hips and knees in preparation.

Once sitting in the half lotus with either leg on top is comfortable, you can progress to the full lotus. Place one foot on the opposite thigh and then very carefully grasp the other knee with one hand and bend the leg in towards the chest while grasping the ankle with the other hand to lift the foot over and onto the opposite thigh into the full lotus. If possible, alternate which leg is on top, gradually extending the time. Gently reverse the process when coming out of the full lotus.

A variation of the head to knee forward bend is the Maha Mudra, which is used, along with special breathing exercises, to stimulate “kundalini” and control sexual energy. After you bring one foot back towards the groin you put both hands on the floor and lift yourself up slightly, sliding forward over the the foot until the heal rests under one side of the perineum.

Note — There is a “Mahamudra” tradition in Tibetan Buddhism that is probably not connected to the above Maha Mudra.

~To be continued~

POST A LINK

If you found this article helpful, or somehow worth linking to in your travels on the www, please feel free to do so. I’m not looking to make any money here, or even to become famous, but like any author it is my hope that someone will read my work and benefit in some way. Thank you.