SELF-DISCIPLINE

“The inferior man conquers others, the superior man conquers himself.” Dhammapada

Most people are disciplined by outside forces and obligations such as job assignments, deadlines and appointments. It’s easier to be disciplined when your boss tells you what to do and your paycheck depends on it.

Most people are disciplined by outside forces and obligations such as job assignments, deadlines and appointments. It’s easier to be disciplined when your boss tells you what to do and your paycheck depends on it.

One of the joys of being a self-employed artist was setting my own schedule. Friends envied my apparent freedom from external demands. What they didn’t appreciate is that painting requires a surprising amount of plain old fashioned, often tedious, work, which must by necessity be self-generated. In order to accomplish anything I had to devise schedules and deadlines — even setting my alarm to get an early start on the day. In other words I was forced to develop self-discipline.

In my twenties I started the serious practice of meditation and yoga, both of which involve considerable self-discipline. Later I took up running and weight training. To some extent I’ve managed to maintain those disciplines into old age, especially meditation.

I also experimented with fasting, which builds self-discipline and makes it easier to regulate the intake of food in general. At one point I gave up meat, fast food, alcohol, caffeine, sugar and every other substance even remotely negative or sinful. I soon started to taste the extra sugar, salt and other additives in foods, which my taste buds had been too jaded to notice.

I even tried total celibacy for a couple of years. Sexual desire has been compared to a fire, and like a fire, when no new fuel is added it eventually dies down. That definitely makes life simpler, if less interesting.

For awhile I lived in a remote location without electricity, which made it easy to eliminate mental stimulants such as TV, phones and other electronics. It’s assumed that running water, appliances and the other gadgets of modern civilization save us time and make life easier. I found just the opposite to be the case. If you really want more time and space, simplify your life.

Self-discipline shouldn’t feel like self-punishment. It’s not necessary to be harsh with yourself and live a Spartan lifestyle devoid of pleasure. Life is actually more enjoyable and rewarding when it’s disciplined. It’s simple things like getting out of bed before sunrise to benefit from the early morning surge of awakening energy or being hungry enough when you sit down for a meal so that you really enjoy the food, but with enough self-control to avoid the negative consequences of overeating.

It turns out that my seemingly herculean efforts with austere practices like fasting, yoga and strenuous exercise regimens was just the easy stuff. The real challenge is simple everyday things that require self-awareness, as well as self-discipline — like paying more attention to others, abstaining from gossiping and bragging, and avoiding bickering with my wife on long car trips. Now we’re talking self-discipline!

I remind myself that only God is perfect (and sometimes I wonder about her) but any improvement we can make in ourselves, no matter how small, redounds to the benefit of the rest of the world.

One of the reasons I’m sitting here writing this is that my own self-discipline has been lagging of late. Just thinking about writing this post has already resulted in some improvement. I’m still far from being a paragon of discipline and self restraint but my ongoing efforts have at least prevented me from sliding into an even worse chaos of overindulgence and excess.

Having spent an inordinate amount of time and energy attempting to tame what looks to be an especially errant and unruly nature, I consider myself something of an authority on self-discipline.

What follows are some basic strategies I’ve learned through my own (ongoing) efforts at self-discipline, along with a little research.

WRITE IT DOWN

Have you ever written out a grocery list, and then when you got to the market you couldn’t find it, but you remembered most of the things on the list anyway? Writing something down imprints it on your brain.

That capacity can be used to good advantage. Making a list of things to do goes a long way towards their accomplishment, as does placing the list where it will be seen and checking off items as they are completed.

One of the most effective ways to lose weight is to simply keep a detailed list of everything you eat. For folks who are trying to save money by spending less, keeping a list of every cent that is spent has proven to be the best way to cut back on expenditures.

If there’s something you would really like to do but are having trouble getting to it, keeping a list of how much time, and when, is spent on the activity is a practical way to accomplish your goal — be it exercise, meditation or some other laudatory endeavor,

Making a list works because it puts what you want to accomplish out in front of you. Putting it in front of you in reality is even better. When I was painting there were days when I just didn’t feel like it but I would force myself to go out to the studio and sit at my easel. I’d start having ideas and before long I was hard at work. Just physically getting to the gym or the desk is half the battle.

VISUALIZE IT

When making a list, it’s good to simultaneously visualize yourself doing the things you want to accomplish. A big part of the brain apparently doesn’t make a clear distinction between a real event and an imagined one. Just rehearsing something in your imagination is akin to actually doing it. But rather than just imagining the end result, envision yourself going through the necessary steps to achieve it.

Several studies have demonstrated that lying on the couch and visualizing yourself exercising has a remarkable amount of the very same benefits as actually exercising. Just imagining exercising a particular muscle twice a day for a few months has even been shown to increase that muscle’s mass and strength by an average of 30 percent of what actually doing the exercise in reality produces. That’s unbelievable until you consider that a lot of what goes on during any activity are internal changes such as the brain’s ability to communicate with muscles, hormone secretion, and even gene activation or suppression.

So although it’s better to actually do something, just imagining it is surprisingly effective. That’s why Olympic athletes spend time visualizing their competitive event over and over before actually performing. It gives them a head start.

The first thing in the morning is a good time to plan out the day and visualize what is to be done. When I began practicing yoga in the sixties I read all of the limited number of books on the subject that were available back then. After learning various exercises and postures I devised my own “routine” which I refined and ran through in my mind every morning while lying in bed. Rehearsing the routine in my imagination made it easier and more effective when I actually did it. Visualization has been a part of yoga and meditation practices for centuries, but it’s only recently, with the surge in neurological research, that such strategies have gained scientific credence.

WILLPOWER

Repeating a particular activity, even if only with the imagination, wires it more securely into the brain. Thus each attempt at self-discipline is worthwhile. There’s no such thing as failure unless one actually gives up and stops trying. Every attempt at self-discipline is a step towards accomplishing it. Even just thinking about it is a step in the right direction.

I started smoking at a young age. After ten years of smoking a pack-a-day, I decided to quit, but it took a year of concerted effort to finally stop completely. I was rolling my own by then and every time I’d decide to quit smoking, I’d ceremoniously empty my tobacco tin into the creek. By nightfall I’d be down on my knees in abject humiliation pawing through the trash for butts. Finally the repeated attempts to quit began to outweigh the acquired conditioning to smoke. Eventually I was able to easily go without cigarettes.

Research has shown that willpower is like a muscle that can be strengthened by repeatedly exercising it. Each attempt, even if it fails, is important for building self-discipline. Every time you force yourself to go to the gym or eat something healthy rather than junk food, you’re changing your brain and how you think.

Like a muscle, willpower also gets tired with overuse. That’s why it’s difficult to resist that drink after a hard day at work. Even self-discipline and willpower need a rest sometimes. It’s like training an animal, one should not be too tough nor too slack, but persistent and consistent.

The importance of willpower and self-discipline cannot be overestimated. It’s an inner strength and ability to stick to decisions that’s essential to success in any undertaking and can overcome addictions, procrastination and laziness.

Although most people would agree that willpower is important, few realize that it can be consciously cultivated and developed. With practice of self-discipline the brain begins to change ingrained patterns of thought and the subconscious starts to help with regulating and overcoming impulses rather than bringing them on.

HABITS

We rely on habit much more than we realize. For instance when first learning to drive a car we had to consciously think about each action, but once we’ve practiced enough driving becomes automatic and effortless. That’s because driving and all the actions it entails is a conditioned habit.

We rely on habit much more than we realize. For instance when first learning to drive a car we had to consciously think about each action, but once we’ve practiced enough driving becomes automatic and effortless. That’s because driving and all the actions it entails is a conditioned habit.

The part of our brain that makes conscious decisions, while obviously vital, is just a sliver of our overall mental activity. Our brains and bodies come equipped with a good deal of built-in pre-programing for the control of basic bodily functions such as breathing and digestion. But most of our functions and abilities are learned and programed into our brains by repetition until they’ve become automatic and unconscious. A simple act such as walking across the room, which we can do without thinking about it, requires so many rapid, sophisticated calculations that if we had to consciously decide every action we took we’d be frozen in place, unable to move, .

In psychology the sub-conscious is traditionally viewed as the seat of repressed desires and powerful archetypal forces festering just below the surface, over which we have little control. I think a more accurate view is to see the subconscious as like a very sophisticated computer that has been programmed by repeated thoughts and behaviors to respond in predictable habitual ways — which fortunately can also be reprogrammed with concerted effort.

When a behavior becomes a habit through repetition and conditioning it stops requiring our conscious direction and instead functions on auto-pilot. How many times have you done a repetitive act like locking the front door or turning off the stove, only to get halfway down the street and wonder if you’d done so? That’s because those simple tasks have become automatic and unless the act is consciously noted the brain doesn’t feel the need to record the event.

The enduring character of habits is crucial. Even though we don’t practice such things as swimming or typing, those conditioned patterns can still be brought up when needed. I couldn’t tell you where any of the keys on the typewriter are, but I can still sit down and type up a storm without thinking about it. Almost everything we do, from riding a bike to shooting pool, and probably even our perception of “reality,” would be impossible without that ability to record and repeat habitual patterns.

The good news, when it comes to eliminating bad habits, is that once they are formed and imprinted on our brain they can be replaced or changed over time, with perseverance and mindfulness. The bad news is that they rarely ever completely disappear. Even when a habit is overcome we must still be on our guard lest it take hold again. Repetition and time are crucial factors in eliminating or adopting habits. It’s said that it only takes about two months of repetition to make something into a habit.

Getting rid of a long term, ingrained habit like smoking can be difficult because the brain will resist changing a habit pattern in favor of what it has been programmed to do. The physical addiction to nicotine is said to disappear after a few weeks but the habitual patterns of behavior keep kicking in. The part of the brain that stores habits doesn’t distinguish between bad and good habits, so if you have a bad one, it’s always lurking there. Unless you consciously fight a habit, the conditioned pattern will unfold automatically.

THE MOMENT OF TRUTH

A crucial moment always arises, when one is confronted with an urge to indulge a bad habit. By paying close attention it’s possible to notice when those moments of choice arrive and remember that one can either reinforce the habit by indulging it or resist it and weaken its hold. That’s a good time to pause and take a deep, breath. Depending on the strength of the urge, it’s possible at that moment to choose to do something else, perhaps substitute a more benign habit. Usually the urge will subside in a short time if the habit is resisted.

If one does succumb to the temptation to indulge in whatever habit one is trying to resist it’s important not to give up completely or beat up on oneself over it. The more one fights a bad habit the less satisfying it will be if it is given in to, which will weaken its hold. Eventually, the repetitive attempts to alter the habit will accumulate and overpower the habitual pattern.

Many habits are combined with other behaviors, involving cues or triggers that kick in the need to satisfy the habit. The classic example is of Pavlov’s dog which would start salivating whenever a cue that was connected to getting food, such as the sound of a bell, would occur. It’s at that point that the habit can either be reinforced or a new habit connection made.

For a smoker, that first cup of coffee in the morning usually demands a cigarette. Linking habits like that increases their power, but that linkage can also be used to replace bad habits with something less harmful. Instead of a cigarette one could eat a banana with that first cup in the morning. At first it won’t feel right. But if it’s repeated often enough, before long the banana will become the habit and if there are no bananas one will have to go looking for one.

If the bad habit is replaced with another more acceptable habit, which satisfies the same urge, the bad habit eventually will lose it’s power. This means changing a normal routine, which can feel uncomfortable and awkward at first.

When trying to establish a new, more beneficial habit, connecting it with an existing habit will facilitate its adoption. For instance, with that first cup of coffee or tea in the morning, instead of surfing the internet, one could make it a time to write out and visualize what is to be done that day. Through the association of one habit with another the brain establishes neural connections that double the strength of both habits.

Habits are also frequently linked with certain times of the day, which act as triggers for the habit to kick in. It’s been shown that if we eat a meal at the same time every day, when that time rolls around, while we might not start drooling like a dog, we do secrete digestive juices and saliva in anticipation. Linking up a pre-dinner cocktail or a desert afterwards can quickly become a habit, as can doing some exercises beforehand or taking a walk after dinner.

Obviously some habits are easier to adopt, than others. Anything that tastes or feels especially good can easily become a habit. The most seductive and immediately pleasurable habits such as sugar, alcohol and addictive drugs, as well as procrastination and laziness, turn out to be negative if continued. Habits like exercise and meditation which can be challenging in the beginning are productive of pleasure later on, producing a host of positive responses and pleasurable feelings brought on by the internal production of powerful natural drugs, such as endorphins and dopamine, that stimulate a cascade of beneficial mental and physical responses.

KEY HABITS

When people start exercising, they also change other, unrelated patterns in their lives, often unknowingly. Research has shown that people who begin exercising also start eating better and become more productive at work. They indulge in other bad habits less and say they feel less stressed. “Exercise spills over,” says James Prochaska, a University of Rhode Island researcher. “There’s something about it that makes other good habits easier.”

If there’s any cure-all it would be exercise. It not only makes one stronger and healthier, it alleviates many otherwise intractable mental issues such as anxiety, depression and poor self-esteem.

Exercise is a key habit that triggers widespread change.

Another key habit is meditation. Just a few minutes every morning sitting up straight, relaxing, and focusing on what is being sensed at each moment, while letting go of rumination on the past and future and the ceaseless flow of discursive thought, has proven to boost willpower by stimulating the areas of the brain that govern decision making and regulate emotions. Research has shown that the effects of meditation are incredibly far reaching and positive.

A key habit that is often overlooked, and one that I’m especially deficient in, is neatness. Just making the bed in the morning has a positive effect on the entire day. A work space that is organized and neat greatly improves mood and productivity.

Neatness is also conducive to mindfulness, another key habit. I tend to concentrate so intensely on whatever project I’m working on that I shut out everything else and stop noticing where I’m putting things or what I’m doing with my body. This results in a lot of wasted time looking for tools, in addition to physical issues from holding uncomfortable positions for too long.

I’m always reminded of an old master craftsman who did some work on our house. He moved at a steady unhurried pace and everything was returned immediately to the proper place in his toolbox. At first I worried he was moving so slow that it would cost me a bundle at his hourly wage. But he accomplished way more in less time than someone who rushes about, scattering tools and wasting energy in unnecessary motion.

SWEET LIMITATION

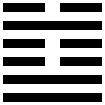

In the I Ching, the ancient Taoist book of wisdom and divination, the Hexagram that comes closest to self-discipline (other than the constant exhortation to “persevere”) is Limitation. The hexagram’s three lower lines, or trigram, symbolize a lake, while the upper trigram represents water.

In the I Ching, the ancient Taoist book of wisdom and divination, the Hexagram that comes closest to self-discipline (other than the constant exhortation to “persevere”) is Limitation. The hexagram’s three lower lines, or trigram, symbolize a lake, while the upper trigram represents water.

A lake occupies a limited space and if more water flows in, it overflows. Thus it shows the necessity of setting limits, which is seen as the backbone of virtue and correct conduct. To voluntarily impose limits on one’s activities and desires is analogous to the Taoist ideal of moderation and the “golden mean” between extremes such as overindulgence and severe self-denial.

The I Ching cautions that “galling limitation” must not be persevered in. If we go to far in imposing limitations on our own nature, that would be injurious. Limits must be set even on limitation.

This is a highly refined form of self discipline — which can be surprisingly difficult. It’s often easier to give up a pleasurable habit entirely than it is to be moderate with it. If something is enjoyable it’s natural to feel that more of it would be even better. Most of my own “addictions” such as a glass of wine with dinner, a couple squares of dark chocolate after breakfast and even the occasional hit of marijuana, are harmless and even beneficial — in moderation. But if they are consumed in unlimited quantities the effects cease to be pleasant and can turn negative. Almost everything, sleep, work, and especially food, is enjoyable and beneficial when limited but harmful when carried too far.

The lower (inner) trigram, lake, in the hexagram of limitation also represents “joy” and the upper (outer) trigram, water, symbolizes “danger.” For someone given to extremes, to be able to enjoy pleasurable habits while still being mindful of the dangers in overdoing them, requires continuous mindfulness. Fortunately, even moderation can become habitual if persevered in long enough.

Another great post zafrogzen. I always enjoy reading them and always find something to reflect on. In terms of the artist and self-discipline, I remember reading the autobiography of the British artist David Shepherd. He described how he nearly cried when he finally understood how much work he’d have to do to be a successful artist. He thought that he’d have a romantic kind of life, but instead found that he would be getting up early and painting until the last of the light, day after day, for much of his professional life.