WARNING: The following contains graphic sex and and drug use, as well as romantic love (which may not be suitable for some Buddhists).

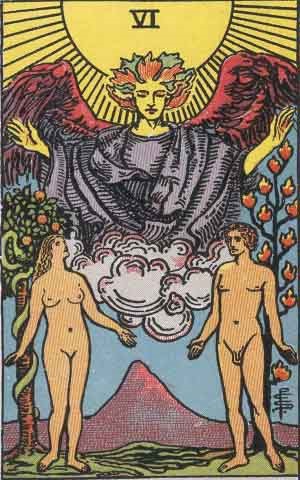

THE LOVERS

How shall I tell it?

Detached from appearances, unmoved, immediate and true

All things are like a dream, a phantom, a shadow,

A bubble in a stream,

Or a flash of lightening

Diamond Sutra

PREFACE

Although I take a guilty, almost voyeuristic pleasure in reading memoirs, I’m somewhat ambivalent in regard to the writing of one. I most admire the great romantic writers of the past who could create an array of fictional characters, bringing them to life and getting inside their heads — even those of the opposite sex. By comparison a memoir seems vain and self-involved.

Nonetheless, I feel compelled to write of certain events and my story would lose its impact if cloaked in the guise of fiction, even if my modest talents were up to such an undertaking,

Instead, I will write as if I were sitting comfortably, reminiscing with an old friend, perhaps over a few bottles of ale and a pipe load of good bud. I have, in fact, been known to hold forth on such occasions, weaving together philosophical observations and short tales from my life as I’m reminded of some incident, individual, or idea which has stuck with me.

It is my hope that you will find something entertaining, perhaps even instructive, in these ramblings.

FROM THIS VALLEY

Jane and Kermit both grew up on small farms in southeast North Dakota where the Cheyenne River meanders across the prairie and joins the Red River as it flows north to Canada.

Jane’s parents were immigrants who came with the wave of Norwegians who settled on the vast farmlands of North Dakota and Minnesota at the turn of the century. As the most recent arrivals, Norwegians were looked down on and Kermit would never tire of teasing Jane with “Norwegian jokes.”

Jane’s father, Julius or “J.O.,” was the offspring of the future king of Sweden and a Norwegian servant girl on an estate that the young prince visited in Norway. This was the cause of some notoriety in that area of Norway and J.O. immigrated to America at the first opportunity, apparently to escape the embarrassment this caused him.

Legend has it he could play by ear, any musical instrument he set his hand to. He was a plump, jovial fellow, who plied the squeeze-box accordion with Polka bands and was fond of drinking the home-brewed beer for which he was also noted.

However, J.O. was ill-suited to farming and “lost the farm” more than once. Jane never got over the dirt-poor poverty of her childhood and was pinching pennies and refusing to spend money on herself, long after she was comfortable financially.

Kermit’s father William and his wife Mary, built a small two story house on a homestead in what was known as the “sand-hills” — marginal land that has since gone back to native prairie grasses. It’s said that you could take a length of pipe and pound it several feet into the ground just about anywhere in the sand hills and heavily flavored artesian water would flow out of it.

On a recent visit to the old homestead, water was still cascading vigorously out of a tall pipe beside a rundown corral. All that was left of the house, which had eventually burned to the ground, was a low concrete foundation.

Long after they had moved on, William would sometimes drive out there for a drink of that water. When he died suddenly of a massive heart attack in his late eighties his body was found nearby.

Ten children were born and grew up in that little house in the sand hills, eight boys and two girls, sleeping two or three to a bed in tiny upstairs bedrooms. The family lived off the land for the most part, with pigs, chickens and other livestock, along with vegetables and grains. But it was a hard life. Kermit, who was the youngest, said that as soon he could walk he was given chores to do on the farm.

Life got even harder with the great depression, when drought and dust storms blew away much of the thin layer of topsoil.

The family made extra money holding dances in a large barn they’d built. Lean times brought people together and dances with live music were everywhere. As a young boy, Kermit sold home-cured ham sandwiches for a nickle at their shindigs, along with “malt” that was mixed with “white lightening” bootleg liquor outside by the watering trough, where muddy fist fights occasionally erupted.

Slender and muscular, Kermit was nicknamed “Curly,” for his luxuriant black hair — which, like his brothers before him, receded back to his ears by his early twenties. Determined to get out of the sand hills, he worked hard in school, even when he had to walk several miles through snow to get there. He was finally able to go off to the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, where he financed his undergraduate education working with the Sioux on a reservation nearby — an experience that solidified his decision to major in Social Welfare.

Jane also excelled in school and longed to pursue a higher education, but she was practical, as well as competent and efficient, so she just took courses at a business college before getting a job as a secretary in Fargo. She was very shy and quite skinny. Like her sister and two brothers, she had hair so blond it was almost white.

Jane and Kermit met at a dance hall in Fargo, during one of those dances that were popular back then, where the men and women move in opposite directions until the music stops and whoever is in front of you becomes your partner. The music stopped and there they were, facing one another for the first time.

Over five decades later they celebrated their golden 50th wedding anniversary at an annual family reunion in North Dakota. In front of a large crowd of relations, Kermit stepped up to the microphone and in a voice hoarse with emotion, told how he was getting ready to be shipped to Europe with the Army when he heard Rosemary Clooney on the radio singing, “I don’t want to walk without you.” He decided then and there that he didn’t want to walk without Jane. He proposed and they were married in an Army chapel. He said he never looked back or regretted walking all that way with her and he gazed across at Jane with such love that just about everyone at the reunion, even his old bachelor brother Orin, was moved to tears.

In their wedding photos they are both glowing with youth and vitality — Kermit, handsome in his uniform, and Jane, slender and beautiful. Kermit had to report for duty the next day and he said they thought, “One night without birth control shouldn’t matter.”

Nine months later I was born.

My mother and I spent the war years with her parents in North Dakota while my father served in France, where he wrote us what was to become a suitcase full of letters. He was a clerk in a Headquarters Company and one of his jobs was tallying the horrific causalities during the Battle of the Bulge — an experience that contributed to his later anti-war sentiments.

As the first born, I was lavished with love and affection. Not only my grandparents, but numerous other relatives who lived nearby, all doted on me.

I was especially fond of my Norwegian grandmother. She was actually a Fin, probably part Saami or “Laplander,” from an area of Norway where many immigrants from Finland had settled. In her later years, she reminded me of an Oglala Sioux, with a beautiful long nose, deeply lined face, slightly Asiatic features, and a long-suffering, stoic, but noble bearing. I remember, as a youngster, lying in her bed, which I shared when we visited, and watching her in a long white nightgown, slowly unfold the bun from her head and carefully comb out her dark hair that reached almost to her knees.

My mother said I was an unusually happy child who rarely cried, even as an infant. Once, when the two of us were traveling on a train full of American troops, the soldiers lifted me up and passed me over their heads from one end of the train to the other, while I squealed with delight.

After my father returned from the war, he went back to school, eventually graduating from the University of Pennsylvania with highest honors and a doctoral degree in Social Welfare. He was soon recruited to teach at the University of California in Berkeley.

As we drove west across the country to California in our brand new, dark green ’47 Plymouth sedan, whose round shape reminded me of a giant turtle, he sang old standards like the “Tennessee Waltz” in a pleasant baritone, while my new little brother, Paul, slept on my mother’s lap and I lay in the sun on the shelf behind the back seat watching the clouds go past.

My parents bought a small house in the rolling, oak tree studded hills overlooking Walnut Creek, which was still just a little village. Facing us across the town below was the majestic presence of Mount Diablo, which was known as “Spirit Mountain” by the Native Americans who had once inhabited the area.

It was wonderful place to grow up, with a lovely tree-lined creek that wound through the town, providing refuge for wood ducks, red-legged frogs and other wildlife. However, in what was my first bitter taste of environmental degradation, by the time I was in high school the Army Corps of Engineers had turned the creek into a lifeless concrete ditch, after it had the temerity to flood one year and inundate some of the downtown with a few inches of water.

While my father commuted to U.C Berkeley, my mom stayed home, keeping the house spotless and catering to his culinary tastes, with delicious home-baked desserts at every meal. She also had to contend with us boys, of which there were now three, since my youngest brother Eric had recently arrived. It was not easy for her. I was a mischievous boy and endlessly inventive when it came to getting into trouble.

After I’d gone off to college, they moved to a lovely old house in North Berkeley where Kermit could walk to campus. Their later years, after he retired, were some of their happiest. They took trips around the country and stayed in B&Bs. Both of them were prodigious readers and they spent a great deal of time reading together on the couch. They got along better than ever, laughing and joking like a couple of newlyweds.

Although my mom had once been high-strung, frequently threatening to have a nervous breakdown if I didn’t change my ways when I was a teenager, in her later years she was as mellow as can be, smiling and laughing at Kermit as if he were a genuine cut-up. “He’s such a dare-devil,” she said, referring, I suspect, to his habit of occasionally climbing up on the steep roof of their two-story Berkeley home to inspect the ceramic roof tiles and perhaps admire the view of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge in the distance.

Not long after their 60th wedding anniversary Jane had a series of small strokes. At first she didn’t seem to suffer any permanent damage, but very gradually over the next few years, her mind and then her body began to fail. Eventually she could no longer be trusted to cook meals, a situation that struck at the very basis of her identity as a wife and mother.

My dad doted on her all the more, looking after her with a “Janie would you like some of this,” and “Janie can I help you with that.” He confided to me that if she died before him he didn’t want to go on living himself.

Finally she came to require full time care. It was suggested that she be put into a nursing home so that Kermit could enjoy his final years. He refused repeatedly, saying, “She would be lonely there.”

Fortunately she had inherited some money from one of her brothers. With that they were able to hire someone to come in daily and help with her basic needs. Although he worked full time, my brother Eric, who lived downstairs, was devoted to taking care of both of them, patiently spoon-feeding his mother every evening after work, before eating his own meal.

As she gradually declined, and could barely speak or sit up, Jane was put on Hospice Care, for those who have only six months or less to live. But somehow she hung on. In one of her occasional moments of clarity she said, with tears in her eyes, “I didn’t know this would be so hard.”

When she hadn’t died after six months Hospice gave her a two month extension. But still she didn’t die, so she was taken off Hospice.

Half seriously, we started to say, “Maybe she’s waiting for Kermit.”

After another year had passed, Kermit suffered a minor heart attack in the middle of the night. He didn’t wake up Eric, and resisted going to the hospital the next day.

I drove down to see him in the hospital. He had refused to let the doctors do anything other than the most basic tests. I encouraged him to do more, pointing out that he was still sharp mentally and not in any pain, but he said, “It’s been a good run, but now I’m ready to go.”

He had often said that too much health care money was devoted to keeping old people alive a few more weeks, while many poor families went without adequate medical care for their kids. He had dedicated himself to improving the lot of disadvantaged children, both as a professor testifying before congressional committees and in his free time as a board member on nonprofit charities dedicated to child welfare.

Driving him home afterwards I asked him if he wasn’t afraid of death. “No,” he said, “The other night as I lay in bed, knowing I was having a heart attack, I shook hands with death. I made friends with it.”

When she was told that he was in the hospital, Jane blurted out, “I’m just wild about that guy.”

After he returned home Kermit tried to continue the routine they had established. Every afternoon, when Jane wasn’t napping, he would lean her up against him on the couch with his arm around her. Sometimes, when she would whimper, he’d sooth her by singing, in a voice cracking with age, the words from the old song.

“Come and sit by my side if you love me,

Do not hasten to bid me adieu,

But remember the Red River Valley

And the cowboy who loved you so true.”

Jane was put on Hospice once again. She had lost almost half her body-weight, but before she stopped eating entirely she had a burst of clarity. For a few days she could respond clearly to questions and seemed to know what was going on. Sitting on the couch with her, Kermit was saying how he would probably outlive her, when she suddenly said in a clear voice, “Don’t count on it buster.”

Kermit had another small heart attack the night before his 94th birthday, and then another a few days later. After the last one he adamantly refused any more trips to the hospital. Weakened and barely able to walk, he was put on Hospice as well.

I came down from my home on the North Coast to spend time with them and take some of the burden off my brother Eric. I recalled how my mom had said years earlier, “I suppose you’ll be there when we die” — like she wasn’t thrilled by the prospect of my presence.

When I arrived she had stopped eating and drinking altogether and although she continued to breathe, she appeared to have left her body completely.

The eighteenth of June, Eric’s birthday, was unusually hectic. Besides the caregiver, I was there while Eric was at work. The phone seemed to ring every fifteen minutes, and Hospice workers were in and out — for interviews, to bathe Jane, and to help in any way they could. They said this was the first time they’d had two people together on Hospice.

We had just gotten my dad up and into his favorite chair in the living room so his bed could be made, when my mother, always a private person, slipped away, dying shortly before noon while no one else was in the room.

I went back and told him, “Mom just died.”

“Oh my,” he said, lowering his head. A few moments later he murmured, “Well, now I can go.”

My mom had died in a hospital bed we’d set up for her in the extra bedroom, with a twin bed beside it for my father. Later that night Eric and I put him to bed in their old bedroom, in the double bed they’d shared for decades.

I curled up on the couch in the living room. For some reason, I woke up around midnight and went in to check on him.

Lying on his left side facing the window, he had died quietly in his sleep.

The lady who came in to clean house for them said afterwards that the last time she was there, “Mr. Kermit” had climbed onto the bed with “Miss Jane” and was holding her.

MY FATHER

When my mom died, while we waited for the men from the mortuary to arrive and take her off to be cremated, I sat on the floor and meditated with her body, which lay on the bed nearby. I thought of how I had once resided in that very body myself and what a deep connection I had with her as a result.

Suddenly, as is said to often happen when approaching death oneself, her life flashed before me, like a vapor trail left behind by a comet. She had suffered quite a bit in her final years and it was almost a relief that she had finally been able to die.

Later that night I also sat crosslegged on the floor waiting for them to come and take my father’s body. A street lamp shining through a lace curtain cast a golden light across the bed where he lay. I bowed again and again to him, thanking him for all he had done for me.

My father was the only person I’d known who was able to love unconditionally, not just his immediate family, but everyone. I’ve encountered famous Zen masters, gurus and other religious figures, but although he didn’t meditate or practice any spiritual discipline, he was still the most evolved human being I’ve known, almost entirely without pride or egotism, someone who listened to others and rarely talked about himself. In short, a saint.

Of course as a teenager I found my dad somewhat embarrassing, with his skinny, nervous frame clothed in an outfit he invariably wore when at home — old faded flannel shirts and the kind of cheap shiny work slacks that janitors wear. His head was almost entirely lacking in hair except for some peeking out of his nostrils and in and around his ears and the back of his head. Now that I’ve lost some hair and gained some in those other areas myself, my appreciation of him has only deepened.

I once encountered a former student of my father’s at a party, who said she’d always wanted to meet one of his children.

“What for?,” I asked.

“Because his ideas about child rearing are so far out, so liberal, I wanted to see how one of his kids turned out.” I think she was disappointed to find I was pretty normal, even housebroken.

I hadn’t thought about it before then, but he really was an unusual parent. He was always supportive, even when my choices were not what he might have preferred. I can’t remember him ever criticizing me. He was there if I needed him, without demanding that I be anything other than who I was.

He never raised his hand against me. He had his own, more subtle, methods.

When I was thirteen or fourteen I started climbing out my bedroom window in the middle of the night. I waited until my parents had been in bed for awhile and then, after arranging my bedding to make it appear I was under the covers asleep, I unlatched the window and slipped quietly out into the night, to creep down the hill in the darkness and throw pebbles at the window of my true love that summer, an overdeveloped young brunette from Texas.

Together we climbed the fence at a nearby community swimming pool, stripped off our clothes and dove into the darkened pool, the water warm in the cool evening air. Chasing one other around, giggling and clutching, making out and playing with each other, I ejaculated into the water, only to worry later that perhaps some sperm had managed to swim into her and get her pregnant.

Other nights I’d meet up with buddies who lived in the neighborhood. Walking the hilly streets under a pale moon was a great adventure. Whenever the lights of a car loomed in the distance we’d shout, “ditch!” and dive into the dark bushes beside the road until the coast was clear.

One fateful summer evening, after one of my nights out, I returned home in the wee hours of the morning and crept around the back of the house to slide my window open and return to my bed.

The window was locked from the inside!

I was thunderstruck, absolutely devastated. I stumbled around the house in a panic, trying to figure out a way to get back in unnoticed. Faced with having to go to the front door, I thought perhaps it might be easier to just run away from home right then and there and become a hobo or something.

After some time, I braced myself and knocked timidly on the front door. After an eternity, my father finally opened the door in his bathrobe. “Where you been?”

“Nowhere,” I replied, slinking off to my room. He never mentioned it again, but that was the last time I ever snuck out at night.

Whenever my father would find contraband I’d hidden, alcohol or sex magazines, he wouldn’t say anything, he’d just take them out of their hiding place and put them nearby in plain sight. When I’d see them and realize I’d been discovered, the blood would drain right out of my head and I’d break into a sweat. My own guilt was the worst punishment imaginable.

My mother, using my father’s own psychology on him, suggested my rebelliousness as a teenager was an acting out of his own feelings towards the establishment. I liked that theory, since it added some credibility to my own general dislike of authority. In fact at the dinner table he did frequently rail against corporations and Republicans, at racism and nationalism — a habit I also adopted as an adult.,

When I started experimenting with psychoactive substances in the sixties he made it clear he didn’t approve. He said that life was interesting enough on its own, without having to resort to drugs. However, he didn’t condemn me for taking them. He gave reasoned arguments against them, most of which later turned out to be accurate.

When I enthusiastically described how LSD opened the mind up to a vast area of experience of which we are normally unaware, he said that there were good reasons for such boundaries, that without limitations the individual self would get lost and life would be chaotic and meaningless — an assessment which was particularly prescient.

He was more tolerant of my enthusiasm for Eastern religious practices, even when I later became something of a fanatic. Driving him home from the hospital after he’d had a heart attack, I said I’d concluded that the ultimate meaning of life had to be personally experienced, it could never be grasped intellectually or put into words — if it could be, there’d be no possibility of salvation in it. He just sighed and said, “I suppose so.”

At one point, after my mother had started to decline, I told him of the Zen masters I’d read about who knew when they were going to die ahead of time and would get their affairs in order, gather their disciples together for final instruction, compose a death poem, and then get into the full lotus and pass away peacefully. He said that when he worked with the Lakota Sioux as a young social worker in North Dakota, he heard stories of some of them who just lay down and quickly died when they were forced onto the reservation.

I realized my father had started preparing for death long beforehand. He’d cleared the house and storage areas of any extra accumulated stuff that wasn’t completely necessary.

Shortly before he died I took him shopping for a pair of pants to replace the one’s he’d been wearing continually. He was adorable shuffling through the department store, wisps of white hair curling down from under the old floppy hat he favored. Back in the car he gazed at the folded trousers we’d just purchased and remarked wistfully, “My last pair of pants.”

When Eric came in and told me that the men from the mortuary had arrived, I got up and walked out of the room and through the house. My nephew Kevin was sitting in a chair by the dining room table looking out towards the bay. As the first grandchild he had been especially close to his grandpa. When I walked into the room he sobbed and burst into tears.

A DREAM

At a very early age, the image of the slender, willowy girl with long black hair was already fixed half-consciously in my mind, like a haunting memory from some previous existence. Even as a young child I seemed to be searching for her, as if I instinctively knew I would find her somewhere in this life.

At an age when most boys showed little interest in girls, I periodically fell madly, obsessively in love. My dream girl always had long, skinny (often dirty) brown legs and dark eyes that danced with mischief and allure. The sight of little, hairless labia enclosing a mysterious slit, that I was occasionally privileged to glimpse through the rumpled leg of a pair of summer shorts, sent me into an ecstasy of almost spiritual bliss.

My intentions, (at least until puberty) were always high-minded. I showered one hapless little brunette beauty with valentines and gifts, even asking for her hand in marriage with a plastic ring from the dime store.

I soon discovered the power of such focused amorous intent. When I fixed my attention on a particular version of my ideal, around the schoolyard or in the neighborhood, circumstances invariably drew us together like magnets. Without a word being spoken we found ourselves running together down a dark deserted school corridor or dashing out of a gathering into a starry night. Suddenly alone together, as if by silent assent we embraced like long lost lovers, our young lips coming together in that first incredible discovery of shared rapture.

The vision of the dark-haired girl was eventually forgotten in the confusion of adolescence when, in spite of my earlier precociousness, I was overcome with shyness around the opposite sex.

Not until I was eighteen would she surface again — this time in a dream.

I dreamt I was riding a bicycle along a country lane lit by golden early morning light. Gliding effortlessly I seemed at times to float blissfully above the bicycle, almost as if I were flying.

The bicycle slowed as I came alongside a lush hedge of flowers and vines enclosing a garden gate. A slender girl about the same age as myself appeared behind the gate. As her dark eyes looked up from beneath lowered lashes a wave of intense longing and recognition welled up from deep within me.

The next thing I knew the bicycle was moving again, slightly faster this time, the country lane widening into city streets lined with gray faceless buildings. A faint but ominous moaning of human voices could be heard, growing gradually louder.

Rounding a corner I came upon the source of the disquieting sound. A small parade was marching up the street towards me, holding aloof a huge photograph, followed by several figures bent under the weight of a dark coffin. As they came closer I realized the photograph they carried was a portrait of the girl I’d seen at the garden gate.

Overcome with a leaden feeling of despair and sadness I turned the bike down a side street and peddled furiously away. The street became narrower and steeper as I peddled faster and faster, until I was hurling over rough wet cobblestones between abandoned buildings that loomed on either side of the dark narrow passage. Suddenly something small and white, an infant, appeared directly in the path of the bicycle. I yanked the handlebars to avoid hitting it and careened out of control, tumbling off into the darkness. I awoke with a start.

The dream so impressed me that I wrote it down and turned it in for a creative writing class I happened to be taking at the time. When it was returned with an “A” I filed it away with other writings and sketches and soon forgot about it.

THE FALL

Like a lot of teenagers, I went though a dark period — or so it must have seemed to my mother. My early attempts at oil painting, of postcard perfect harbors and country roads, quickly gave way to large expressionistic works of agonized figures, executed with thick, slashing, impasto. I even attempted to write poetry, with somewhat less success, but with the same images of strange figures, often falling or sinking into a nameless abyss.

I had discovered blues music and I stayed awake late into the night lying on my bed listening to the rhythmic wailing and moaning of love lost and hopes betrayed, broadcast over KDIA from the black ghetto in nearby Oakland. I was distressed to live in such comfortable circumstances and was sure that no great art could ever come out of middle-class white America.

My social life consisted primarily of hanging out at the pool hall downtown and binge-drinking on weekends. We had moved into a new house just up the hill and I now had a bedroom downstairs with a separate back entrance so I could stagger in drunk at all hours without waking anyone. After getting into bed I’d frequently get the tailspins, like a plane going down in flames, falling back into dark space with a wonderful feeling of abandon and letting go — which unfortunately was usually followed by the urge to puke.

No matter how far down the toilet I stuck my head my mother could always smell vomit the next day, so instead I’d lurch out the back door, across the damp lawn, and hurl barf over the embankment into the bushes below.

One night, after bending over with a violent bout of the dry heaves, I awoke with the morning sunshine beaming down on me and the sound of the neighbors puttering around in their yard.

I was lying sprawled at the edge of the lawn in my white jockey underpants.

I jumped up and scurried back inside, wondering if my father might have already come to the big window above, looked down, and perhaps in disbelief called out, “Jane, isn’t that Stephen down their sleeping on the grass in his underpants?” If so, he probably thought it served me right, and left it at that.

It’s a good thing drugs were not readily available in the 1950’s or I might never have made it to adulthood. I seemed to be seeking some kind of oblivion, or at least an altered state.

What must have finally forced my mother to call upon the church to attempt a rescue was my choice of reading matter. Not just existentialism and Gnosticism, but Vedanta and Buddhism, Zen and Sikhism, as well as the likes of Jack Kerouac and Bertrand Russell.

She informed me one day that she’d asked Pastor Toleffson to come by and have a talk with me. I didn’t protest. In fact I’d been having conversations with the good Pastor in my head for some time and I welcomed the opportunity to air some of my concerns about the direction of contemporary Christianity.

I’d always liked Pastor Tollefson. He was a stout Scandinavian who radiated kindness and humility and was genuinely sincere in his beliefs. I think I was probably one of the few people who actually listened to his sermons without falling asleep. I found him thoughtful and at times even inspirational, in spite of my own heretical tendencies.

What I hated about going to church, besides having to get up at such an ungodly hour on Sunday morning, was the hard wooden benches the congregation was forced to sit on for what seemed like an eternity. Ironically it wouldn’t be long before I was getting up even earlier to voluntarily sit erect, with legs painfully crossed, in the pursuit of religious awakening.

My mother had cajoled and coaxed me out of bed every Sunday for years with the promise that when I finally went through the ceremony of “Confirmation” at fifteen I’d be a full fledged adult member of the church and could make up my own mind if I wanted to continue going or not. Much to her disappointment, except for the annual candlelight service every Christmas, I stopped attending church regularly right after confirmation.

When Pastor Toleffson came down the stairs to my room I was at my easel working on a large oil painting executed in bold jagged shapes. He hadn’t seen me for some time and looked surprised at how much I’d matured. Although still slender and fresh faced in spite of a faint hint of early whiskers, I was now a tall young man with small but distinct biceps bulging from out of a ragged, paint stained tee-shirt. My dark blond hair was longer, combed back on the sides, with a loose wave hanging over my forehead in front. The room smelled of turpentine and cigarette smoke, a combination that must have struck the pastor as decidedly dangerous.

“I haven‘t seen you lately, what have you been up to?” he asked.

“Huh, I’ve been reading a lot about other religions — Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism,” I replied, “It looks like they all lead to the same place.”

“There is only one way to find God, and that is through our Lord Jesus Christ,” he said firmly.

I hated it when they made that claim, which seemed like a veiled threat. Either get on-board or suffer an eternity in Hell. It was hard to respond to such confident certainty.

“What are you painting?” the Pastor asked, changing the subject.

“Its called The Fall.”

“Hmm,” he said squinting at the jagged shapes and raw colors that formed a large figure falling backwards and downwards across the canvass, “Nice colors.”

He left without saying much more. He probably figured he’d done enough to satisfy my mother and that it was fruitless to waste any more time trying to bring the likes of me back into the fold.

I think I had been something of a thorn in his side during Confirmation Class, the required period of bible study preparatory to becoming a full fledged member of the Lutheran Church. Parents naturally want their children to share their spiritual beliefs, and my mother was no exception. Following the example of my father, I went along with it, intending to do the bare minimum necessary.

But once I started reading the new testament I couldn’t help getting involved.

At one point when the Pastor was going on about how Jesus had “died for our sins,” and what an immense sacrifice that was, I blurted out an objection, “Getting hung on a cross must have been a painful way to die, but people die painful deaths everyday. Jesus got to go right back up to heaven. Where’s the sacrifice in that? If he had just died and disappeared, or worse, gone to hell, now THAT would have been a sacrifice.”

“He was the Son of God,” the pastor exclaimed, “He came so that we may have everlasting life.”

I couldn’t help but be moved by Pastor Tollefson’s sincere religious feeling. It was like tasting a fine wine. But it was his own personal emotion that I responded to — not the story that triggered it. No matter how wonderful and heroic that story, and the dogma that surrounded it, I felt something was missing. Although I was entranced and inspired by the words of Jesus I suspected his story had been added to after his death in order to turn him into something other than a mere mortal, which to my mind actually lessened his significance. The notion that salvation was found through somebody else, and furthermore that it was something that was experienced only after death, struck me as a chancy proposition.

That hadn’t stopped me from having visions of Jesus. Not major ones, just quick sightings out of the corner of my mind. I’d see him sitting on a stone wall or at a rough, wooden table in a crowded inn — a charismatic figure who seemed to exist in an exalted state of indescribable bliss that I was somehow able to share for a brief moment.

I should say a few words about “visions” because they also figure in later parts of my story. In those days a vision was not something I could just decide to have anytime I felt the urge. They were spontaneous unplanned events that swept me up and out of my usual narrative, while still somehow managing to fit seamlessly into the normal course of life.

Such experiences were internal and accompanied by a feeling that was strangely visual and can only be described as ecstatic or blissful. They had a timeless quality, although they were usually brief.

Some of my visions could be ascribed to an overactive imagination, triggered by something concrete, such as my exposure to Christianity. However, at other times they were more subtle and harder to attribute. They might involve real people whom I didn’t even know. I’d be walking through the neighborhood on my paper route and I’d suddenly find myself, for a brief moment, in one of the homes nearby looking out through another person’s eyes.

The most provocative vision, which recurred several times throughout late childhood and early adolescence, involved a disembodied person or presence, like an “imaginary friend” described by some children. I’d suddenly be drawn, as if pulled by a mysterious voice, to hidden spots under trees beside a tiny stream or across hillsides to protected gullies, where I would spontaneously sit cross-legged on the ground as a “being” appeared to me. Not a physical being, more like a being of light that nonetheless felt like a real person appearing both inside my head and up above in the space in front of me, who would wordlessly guide me to a state that can only be described as meditation — completely present in the moment and the immediate surroundings but at the same time infinitely expanded internally until time and space became meaningless.

Looking back, these experiences seem unremarkable — no words of wisdom, no golden tablets or anything of that sort. Just sitting quietly along with my visionary friend, looking out through my eyes with a clear mind, enveloped in an indescribable feeling of peace and happiness.

Later, when I read about Tibetan Buddhism I was struck by the similarity to the practice of visualizing meditation deities and gurus in the same manner. Was this a memory or visitation from a previous lifetime — or perhaps a glimpse of a future self?

Such experiences were especially frequent and powerful when I was approaching puberty, after which they quickly diminished and finally almost disappeared altogether. It was as if a part of me, a way of seeing and being in the world as a young child, was breaking up and dissolving, and the visions were scattered fragments or brief regressions to that earlier state, which was disappearing under the weight of adolescence and early adulthood.

I felt as if my mind and perception, which had been innocent and open, peaceful and blissful in childhood, was being poured into a funnel and narrowed down to a rigid self-conscious entity, constantly engaged in thinking and worrying.

Where the movement of time had once been wonderfully slow and spacious, now it was speeding up, making the days seem progressively shorter.

I assuaged my adolescent angst by reading voraciously, often into the early morning hours. With a stack of my mom’s cookies and a tall glass of milk, I plowed through classic romantic novels, Jude the Obscure, The Red and the Black, Crime and Punishment, Les Miserables, along with more philosophical works such as Being and Nothingness, Thus Spake Zarathustra, The Upanashads, and many others.

I was especially drawn to books on Eastern Religions, where salvation is seen as something that already resides within everyone, without exception. All that was needed I thought, were the proper techniques.

The first time I saw an image of a figure in meditation, a photograph of a stone statue from India sitting in the half lotus with open hands on its lap, I was transfixed — a perfect expression of peaceful grace and equipoise.

THE MONK AND THE PROSTITUTE

“Have you thought about how you’re gonna fulfill your military obligation?” The question came from Dave Pond, a short, freckle-faced kid who lived around the block from us, whom I’d known since we were in the third grade.

“My what?”

“Your military obligation. Everyone’s gotta go — or get drafted into the Army.”

It was 1960 and we were about to graduate from high school. Dave said he was joining the California National Guard. He suggested we both enlist in what was called the “buddy system,” which meant we could go through it together. “Only six months active duty and then a couple of evening meetings every month for a few years. Better than getting drafted for two full years,” he insisted.

I was dubious but since we were buddies I let him talk me into going down to the local armory to see the Recruiting Sargent. The armory, into which I’d never ventured before, was surrounded by pavement and various boxy brown military vehicles and equipment. We entered by a large unmarked metal door. The inside smelled faintly of leather and boot polish.

Crossing an impressive expanse of shiny hardwood floor to a small office, we met the Recruiter, a wiry little Sergeant encased in starched olive drab fatigues.

I told him I wasn’t sure yet if I wanted to join or not, that I was also considering going into the Forest Service up in Idaho where my cousin was working. I could get a job there on a fire crew for the summer before I started college in the fall.

“No problem,” said the recruiter cheerfully, “Join the National Guard, start going to meetings with us one night a week. Try it out. If you change your mind you can still go to Idaho. We’re a California Organization so we’ll automatically let you out of the Guard if you move out of state.”

“What the heck,” I said, “I can always get out of it if I don’t like it.”

He insisted on signing us up on the spot. I even felt a little burst of pride when I easily passed the mental and physical tests.

I hated it. The meetings were incredibly boring. When we weren’t standing around waiting for whatever was scheduled next to get organized we were cleaning and polishing the various military equipment scattered about the premises. It was worse than the Boy Scouts, which I’d also quit after a few meetings.

So right after graduation from high school I told the California National Guard I’d decided to move to Idaho to work in the Forest Service. Feeling somewhat sorry for Dave and the other guys, but glad to be leaving, I returned the boots and fatigues they’d issued me and got ready to go to Idaho. I packed a single suitcase with some work clothes, a new pair of steel-toed boots, and several paperbacks by the likes of Friedrich Nietzsche and Albert Camus, weighty for their content if not their size.

Among the books was one that would leave a lasting impression on me — “Thais,” by Anatole France, the story of a beautiful courtesan and a Christian monk from the desert who tries to reform her. She dies and because of her pure heart she ascends directly to heaven, while he goes mad with unsatisfied lust.

After a long bus ride through Oregon and Washington, spent half asleep staring out the window at stunted, closely-spaced trees whizzing by, I was deposited in the tiny town of Avery, not much more than a post office, in the upper panhandle of Idaho. From there I hitched a ride down a dusty gravel road that wound alongside the Saint Joe River, flowing wide and quick over round boulders. The air was sparkling clear and fresh with the resinous smell of fir and cedar.

The remote fire station that was to be my home for the next three months was set in a small meadow in the center of a large expanse of wilderness. Our job, when we weren’t putting out the multitude of fires that were ignited every time there was a lightening storm, was to tediously clean up the branches and debris left behind after big logging corporations clear-cut huge swaths of pristine forest. I couldn’t help but wonder who picked up the bill for our work.

In Idaho I would learn a little about two mysterious and potentially dangerous creatures — bears and women, in encounters that were both exciting and aerobic.

First the bears.

I’d barely unpacked my suitcase before I was treated to bear lore and bear stories. Black bears were almost as common as the huge elk that were constantly charging across the road before our trucks.

Grizzly bears, while less prevalent, were far more dangerous. One woodsman from the area was reputed to have had the presence-of-mind to play dead, closing his eyes and going limp when he was surprised by a grizzly. The grizzly just chewed on his arm a little and walked away. That’s what you had to do I was told in utter seriousness. If a grizzly grabbed hold of you just play dead.

You can never outrun a bear on level ground or uphill. For a short distance, about a city block, they can move faster than any human being.

Downhill was another matter. Because their front legs are shorter than their hind legs, going downhill is awkward for them.

But the best thing to do if a bear takes after you is to climb a tree. Not just any tree though. It has to be a skinny tree, one that’s small enough in diameter that the bear can put his arms clear around it. Apparently bears can only get a good enough purchase on larger trees. Plus small trees have branches extending down lower, making them easier for humans to climb.

I would have occasion to test both of those theories in person.

There were twenty young men on the fire crew that summer and we had our own full-time cook who specialized in serving up heaping platters of T-bone steaks. The station brought in whole sides-of-beef to feed us and the remains were thrown onto a dump in the nearby woods, which of course was a favorite haunt of the local bears.

Late one afternoon I had the bright idea to test the “a bear can’t climb any tree it can get its arms around hypotheses.” Armed with a long rope, a couple of us climbed carefully selected trees at the edge of the dump, where a big pile of fresh bones and beef trimmings had been deposited.

Right on schedule, just as the sun was getting low, we heard the crashing and thumping of bears coming down through the underbrush. Apparently bears don’t have any natural predators, so stealth is not a concern for them.

They were not quiet eaters either. Listening and watching them snort and chomp loudly as they devoured the beef scraps, from our perches about twenty feet above them in our little trees, was immensely entertaining.

Finally, I decided the time had come to see if a bear could actually climb a tree it could get its arms around. I tied the end of the rope into a lasso and after several misses I managed to drop it around one of the biggest and blackest of the bears.

I’d tied the other end of the rope to the tree just below me. When the bear tried to move away the whole tree shook and threatened to come down with him. With that he realized he was attached to the tree overhead. He stopped and looked up at me sitting there. With a thunderous roar he attacked the base of the tree and started to climb it.

I began to wonder if I should try to move higher up my skinny little tree or whether it was possible to leap over to another tree.

But sure enough, after climbing several feet the beast faltered and couldn’t go any further. With that he dropped down and proceeded to vent his furry on the rope, shredding it in a matter of moments. With one final roar of indignation the bear rumbled off the way he’d come.

Not long after that adventure, on a sunny day off from work, I took a hike up to a fire lookout tower on a nearby peak. After chatting with the young chap who manned the lookout, whose solitary lifestyle I envied for the opportunities it provided for meditation and reading, I headed back downhill on the narrow switchback path I’d hiked up earlier.

Walking along the side of a steep slope covered, appropriately, with tall “bear grass” native to that area, a huge bear suddenly stood up, only a few feet uphill from me. It’s height, due partly to the upward slope, looked to be seven or eight feet tall. It gazed directly down at me.

Another caveat might be — never look a bear in the eye. As it silently dropped down towards me I leapt off the trail in the opposite direction, down the steep side of the hill, running like I was falling, my legs spinning to keep up with me.

I heard the bear thundering behind me for a minute or two but it couldn’t keep up. As it turned out, it really is true that bears can’t run fast downhill — but I sure as hell could. Ignoring the switchbacks in the trail I shot straight down the mountain. I didn’t stop running until I’d arrived exhausted back at the Fire Station.

I’d had enough of bears. I was ready for some women.

One weekend several of us firefighters traveled north to Wallace — a wild grubby logging town of dirty brick buildings and smelly barrooms, where prostitution was apparently legal or at least openly tolerated. There were establishments with names like the U & I Rooms and the Come On Inn, with half-naked women beckoning from upstairs windows.

With several drinks under our belts to buck up our courage we picked one of the more respectable establishments (if such a term can even be applied here) and climbed the stairs to a dingy waiting room.

As we sat back, the “girls” paraded into the room one by one for our perusal, wearing only lacy undergarments.

I held out til the last. I never could buy any item without first examining each and every one that was available. Also, I thought that this might be my first time, that technically at least, I was probably still a virgin since I was not really sure if I’d ever actually completed the act in my numerous forays, usually executed half-drunk in parked cars.

I was the only one left in the room when a raven-haired woman in red lace sashayed through the door and held out her hand seductively in my direction.

Somewhat apprehensively I stood up and followed her wiggly behind down a long hallway to a small private apartment. It had a comfortable lived-in look that made me think she must actually reside there.

Quite a bit older than me, she was still attractive, with smooth very white skin and slightly plump thighs and tummy. She carefully filled a basin on a low washstand and told me to undress.

Taking my already erect penis in her hand she gently pulled me towards the washstand where she began to wash it, almost tenderly, with warm, soapy water. With a loud exhalation I ejaculated.

“Is this your first time,” she giggled.

“Yeah,” I admitted, shamefaced.

“Well, we’ll have to give you another shot at it then.” On her bed, engulfed in sweet perfume and soft flesh, I lasted long enough to begin to get a feel for the rhythm of it.

Afterwards, instead of rushing me out for another customer as I’d expected, she lingered with me on the bed for some time and talked. She confided that, yes, she was hooked on heroin, which is why she was in this particular profession, but this was a very clean establishment, with all the girls getting regular medical exams.

Before we parted she reached into a cupboard beside the bed and pulled out a stack of neatly folded tee-shirts. “These were left here,” she said handing them to me, “They’ve all been washed.” I was profoundly touched and wore them proudly after that, even though they reeked of her perfume and some of the other firefighters made unflattering comments.

I would have one more close encounter with a bear, when our entire crew hiked for several arduous hours up a steep ridge to spend five exhausting days fighting a blaze that was over five acres and threatening to engulf the entire area. We worked twenty hour days with only a few hours of sleep sprawled on the fire line.

In the middle of the night I left the still glowing fire, barely contained in our hastily constructed fire break, and walked into the surrounding forest to relieve myself. As I blindly made my way through dense brush and pitch black darkness, I suddenly slammed nose deep into a wall of soft fur — the chest of a large bear standing in my path. I turned and ran, while the bear fled into the darkness going the opposite direction.

CAR WARRIORS

When I returned home from Idaho there was a letter waiting for me from the “Department of the Army.” It looked official — and ominous. Was I getting drafted?

I tore it open. Inside were orders to report for active duty.

Reading further I was somewhat relieved to learn I’d been inducted into the Army Reserve for six months active duty rather than the minimum of two years required by the regular Army. That weaselly recruiting Sergeant hadn’t outright lied, he’d just neglected to tell me the whole truth. If I moved out of California to work in Idaho I’d be discharged from the California National Guard all right. What he didn’t mention was that I would automatically be transferred into the United States Army Reserve.

My naivete was embarrassing. Adults in my life up till that point had been scrupulously honest, unlike some kids I knew. Somehow (incredibly) I was under the impression that all adults were truthful.

I crammed as much partying as I could into the few weeks I had left before reporting for duty at Fort Ord, a sprawling Army Base a few hours to the South on the coast near Monterey. When I stepped off the bus at the Fort’s induction center, along with a contingent of other nervous new recruits, we were greeted by a cadre of Drill Sergeants who were apparently violently angry at the very sight of such a slovenly crowd of “cruits.” Shouting and cursing they herded us through a daylong series of stations to be issued a duffel bag full of clothes (between long boring periods of waiting in line) and run through a gauntlet of handheld injection guns for distributing various immunizations. With blood dripping down our arms from injections fired without good skin contact, our hair was unceremoniously mowed to a stubble and we were assigned to various units for basic training.

When the the black Platoon Sergeant from Louisiana greeted us at our barracks he drawled, “You can send your heart on to God, because your ass belongs to me.”

Although I hated the Army, I’ve since joined the ranks of those who think it’s a good thing for young men just starting out in life to be subjected to an intense period of discipline and physical conditioning. When I reported for active duty I was 142 pounds of flaccid flesh. After three months of basic training I emerged with 170 pounds of pure lean muscle on my six foot frame. My neck, once a chicken-like protuberance, came straight up from my shoulders like a tree trunk. I could do push-ups and pull-ups practically indefinitely.

Army food was surprisingly good and long hours with frequent bouts of vigorous exercise stimulated a ravenous appetite. My favorites of chipped beef on toast (“shit on a shingle”), or roast turkey with all the trimmings, were served almost every week. In the mornings there was all the pancakes and scrambled eggs and bacon we could eat.

For someone who’s biological clock was set to sleep in as late as possible, the shock of being abruptly woken up before five every morning by loud insults, forced to quickly dress while still half asleep, meticulously make the bed in an auditorium-sized room full of double bunk-beds, and then be standing at attention for inspection in a matter of minutes, was a radical and bracing change from my previous teenage existence.

Before breakfast we jogged several miles through sand with heavy rifles held up in front of our chests. If anyone fell behind, which a few fatsos inevitably did, two of us had to grab them under the arms and drag them along with us, which didn’t exactly increase their popularity. After a couple weeks of torture and abuse by Drill Sergeants trying in vain to whip them into shape those few stragglers disappeared, to be mercifully discharged as “physically unfit.”

Whenever someone slipped up or made the slightest mistake a Sergeant would yell “gimme ten” — meaning pushups. Looking back, although loath to admit it at the time, I think I developed a taste for rigid discipline and strenuous physical exertion. Pushed to the extreme of mental and physical exhaustion, along with the likely release of stimulative brain chemicals, my usual mind of repetitive discursive thinking occasionally simply gave up and emptied out into the present moment with a sudden indescribable transcendent bliss. I had several deep religious experiences in basic training, which although brief or momentary, I still savor.

Relentlessly marched to classrooms, obstacle courses and shooting ranges from dawn to dusk, we collapsed on our bunks immediately upon the order of “lights out!” If a recruit fell asleep in one of the incredibly boring classes we were forced to endure, a Sergeant would take delight in sneaking up on him and bellowing an insult while slamming down both fists loudly on the desktop — much to the amusement of the rest of us. I soon developed the amazing ability to sleep with my eyes wide open, which I think might have contributed to a tendency later in life to sit up and talk in my sleep with my eyes open.

Besides the shorn hair, recruits wore brand new, baggy, dark olive-green fatigues and floppy Sad Sack caps, all of which stood in stark contrast to the Sergeant’s attire. In those days, before the advent of camouflage fatigues and wide-brimmed hats, Drill Sergeants wore crisp short-billed caps and fatigues bleached and faded to a beautiful silvery-green and so heavily starched that the creases projected in sharp-edged lines down the outside of their arms.

Drill Sergeants were the elite of Fort Ord. Compared to them commissioned officers were slouches who only showed themselves for ceremonial occasions. Our company was headed by “Krebs,” a lean hawk-nosed Master Sergeant who was universally feared and respected. Although he must have been over forty he could do pushups using only one arm for longer than most of us could with both arms.

The practiced verbal abuse was delivered with dark humor and perfect timing. Constant regimentation, standing at attention in straight lines, mass calisthenics and marching in step to loud cadence counting, was all designed to diminish our individual humanity in the service of molding us into a homogeneous fighting force of platoons and battalions that could be mobilized and moved into action by higher-ups, like any other machinery of war.

The only concession to individuality was a white patch sewn on the right chest with a last name in black letters. Thus everyone was referred to by their surname. Friendships were formed haphazardly by who happened to be standing next to you in line or sleeping in the bunk below. My closest friend in basic, who I knew only as “Gardner,” was a big strapping hillbilly from Kentucky. He had impulsively enlisted for three years in the Army and Green Beret training in response to his girlfriend breaking up with him. I don’t know if she ever regretted her decision, but he certainly did — at least while I knew him.

Near the end of basic came the most rigorous class of all — Prisoner-of-War Training. After some preliminary maneuvers our entire company was “captured” and marched into a stockade with armed guards posted along its high walls. We were forced to stand perfectly still at attention in the hot sun for hours to be taunted by the “enemy” — in the person of a charismatic black sergeant who was famous throughout Fort Ord for his karate chops. Whenever anyone wavered or protested the verbal abuse, his hand flew out and hit the side of their neck with a loud “thwack,” at which point they collapsed and lay on the ground twitching spasmodically. That was the signal for the guards along the walls to fire their weapons into the air and drag the unconscious prisoner away by his feet.

Finally we were allowed to “escape” and rendezvous back at a small auditorium where we sat facing a wide glass wall on a stage. When the lights were turned out and a light went on behind the glass, we realized it was a two-way mirror. In the narrow room on the other side of the glass wall, which the people inside apparently couldn’t see out of but was lit up like a theater for us, was a large chair like those in a barber shop, with wrist clamps on either arm and dangling wires and dials on the wall behind.

One by one the prisoners who had been knocked out and dragged from the stockade were brought in for interrogation. We’d been advised beforehand that if we were captured to only give out our name, rank and serial number and not to reveal any other information, such as what company or battalion we belonged to.

As we all watched, wires were attached to each prisoner in turn as they were sat in the chair. When they refused to answer a question put to them by the interrogator a strong jolt of electricity was administered. It didn’t take long to get them to give in and reveal whatever information the enemy wanted.

Only one prisoner held out — a slender bookish draftee with a masters degree in literature. Quiet and unassuming, he was the last person you’d expect to engage in heroics. They gave him jolt after jolt until his legs shot straight out in front of him, but he refused to answer any of their questions.

Finally they gave up and turned the lights on in the auditorium so he could see the rest of us — as we all stood up applauding and hooting loudly.

It was hard to ignore what the Army was all about. During marksmanship training we aimed at targets in the shape of human silhouettes. With my natural artist’s hand/eye coordination I easily qualified as an expert marksman.

When I was around nine years old, one of my uncles gave me a BB gun. I soon got bored with shooting tin cans and started aiming at birds. I hit a tiny gray and yellow bird (probably a Wilson’s Warbler), which fell from it’s perch in a tree overhead and lay mortally wounded at my feet. As I picked it up, still alive and warm in the palm of my hand, its tiny round eye gazed up me with palpable pain and fear.

Somehow I managed to put the little guy out of his misery, but that look in its eye has never left me. Even now, so many decades later, I still feel deep regret whenever I remember it. I can understand how some veterans are haunted by what they did in combat long after returning home.

On the last day of basic training we were allowed to go the PX for the first time and buy beer. We were told that we had the whole barracks all to ourselves for the next 24 hours and could do whatever we liked to celebrate the completion of that phase of our training. We were no longer “cruits” but bonafide soldiers.

Early in basic the drill sergeants had divided every platoon into four squads of about a dozen men apiece. Then they appointed one of our fellow recruits as the leader of each squad and gave him a temporary slip-on arm band with a corporal’s stripes. I don’t know if it was the result of deliberate selection on the part of the sergeants or just human nature, but the newly minted corporals soon let their newfound power go to their heads.

Taking abuse from genuine drill sergeants with years of experience was one thing, but we bristled when taking it from a fellow recruit, which only drove the “corporals” to greater excesses of verbal bullying and oppressive demands. The drill sergeants did little to rein in the little monsters they’d created — until that final day of basic training.

The evening of our “anything goes” last day of basic I broke out a full canteen of “GI gin” that I’d been saving up for just such an occasion. Fort Ord, with it’s cold dank coastal climate, was a breeding ground for germs. Many of the recruits were coughing up pale green loogies the size of small frogs. Anytime someone went on sick-call, for whatever reason, they were given a bottle or two of codeine cough syrup — which a few of us had collected and emptied into a water canteen.

With several other kindred spirits I was sprawled along a polished hallway floor, leaning against a wall and passing a canteen of GI gin/codeine back and forth and washing it down with beer — when one of the former corporals, bleeding profusely, came screaming down the hall past us. Apparently some of our comrades had exacted retribution for the abuse they’d received at his hands. I’m sure the drill sergeants knew this would happen and perhaps even relished it as a final lesson in military customs.

I hate to admit it now, but as a teenager I was an avid fan of fistfights — although I usually managed to avoid them myself. In high school a couple of guys were like mythical gunslingers in the old west, renowned far and wide for their fearsome ability to dispatch opponents in fights, oftentimes before huge crowds after school.

Somehow I became buddies with one of the most noted brawlers. He wasn’t especially big, size-wise, and quite ordinary in appearance, but Jerry Corso would go crazy in a fight and no one could stand up to him, no matter how big and tough they were. He was particularly incensed by anyone who put on airs and acted “bad.”

One time the two of us were walking in town when a big muscle-bound guy with an elaborate pompadour gave us a condescending sneer as he swaggered past us in a tight tea-shirt with a pack of cigarettes rolled up in one sleeve. Without a word Corso turned around, grabbed him, threw him up against a nearby wall, and pummeled him with a quick flurry of blows that left him sliding down the wall to the pavement.

At the annual Walnut Festival, an eagerly awaited event which featured a big carnival near the Civic Center, the Hells Angels motorcycle gang traditionally made an impressive entrance on Friday night. As they cruised slowly down the street one year, in a long double line of customized Harley “choppers,” arms hanging languidly from high handlebars, revving their engines and looking incredibly bad, Jerry Corso suddenly shot out from a crowd of spectators on the sidewalk and proceeded to kick over motorcycles and riders right and left before disappearing across the other side of the street — leaving Hells Angels and their downed choppers sprawled awkwardly all over the pavement.

As a teenage fight fan I always eagerly awaited the Friday Night Fights on TV. It was the golden age of boxing, with the likes of Archie Moore and Sugar Ray Robinson defending their championships. I even got some boxing gloves of my own and organized matches with neighborhood kids, sometimes getting in the ring myself or at other times acting as referee, announcer and timekeeper. For awhile I trained my younger brother Paul for matches with other kids his age, whom he easily beat with his natural speed and coordination.

After we got out of basic training, and had been assigned to new units for further training, there was more time and freedom to explore Fort Ord during off-duty hours. I soon discovered a completely equipped gymnasium and arena where boxing matches were held every Friday night. Any soldier on the base could train there to fight a few rounds before spectators in a professional looking boxing ring, with their own trainer in the corner and a colorful silken robe to make a proper entrance.

I was initially set on signing up myself, but when I perused the other fighters in my weight class working out, lean muscular black guys with blazing speed and power, I decided I’d do better as a trainer and coach. The heavyweight division looked to be deficient in talent and at six foot four, two hundred and twentyfive pounds, I thought my friend Gardner could be a promising contender. I easily talked him into signing up for a heavyweight bout and proceeded to coach him at the gym on the finer points of the pugilist’s art. I even got him up early in the mornings prior to the bout to run several miles with me.

The night of the fight I was pleased to see that his opponent was a flabby overweight white guy. When Gardner entered the ring and took off his robe an audible gasp went through the crowd. He had shoulders like soccer balls, big bulging biceps, magnificent pecs, and a perfect six-pack of abs.

The fight was only four rounds, but once it got under way it was easy to see that Gardner was not championship material. He was slow and awkward and by the second round he was so winded he could barely stand up straight. But his adversary clearly knew his way around a boxing ring, and despite his flabby physique, had very fast hands.

Gardner was still standing when the referee mercifully stopped the fight with a Technical Knockout (TKO) at about the same time that I was wondering if I should throw a towel into the ring.

The following week I took Gardner to the nearby city of Seaside and treated him to a night on the town to make amends for having persuaded him to get into the ring. After much food and prodigious amounts of alcohol we stumbled across a seedy tattoo parlor on a back street. “Let’s get tattoos,” I exclaimed.

Inside, before a wall of possible tattoo designs, Gardner settled on a large winged Airborne Special Forces insignia for his right bicep.

As I dizzily tried to choose between a small rose or a dragon for my forearm, the tattoo artist sat Gardner down on a stool near the front window and went to work on his bicep. As the image took shape I moved in for a closer look.

Without pausing to look up or shut off his humming electric needle, the tattooist calmly reached behind his back with his free hand and pulled out a plastic bucket — just as Gardner started to vomit uncontrollably. The rising stench filled my nose and I started to throw up myself before quickly lurching out the door into the fresh night air, where I could safely watch the tattoo being finished through the window.

When Gardner came out, looking pale, but proudly showing off his tattoo, I said there was no way I was going back in there and getting one myself.

The new unit we were assigned to for Advanced Infantry Training (AIT), was remarkably easygoing after the rigors of basic. Our platoon sergeant, a reclusive and gentle soul with a severe stutter, seemed just as reluctant to show up for duty as the rest us. Whenever he was spotted coming towards the barracks looking for “volunteers” for kitchen duty or other similarly unappealing work, everyone dove for cover, squeezing into the tall lockers that lined the walls or sliding under beds. Where basic training had been strict and tightly organized, what followed was so muddled and undisciplined that it was almost fun — unless the prospect of actually going into combat under such circumstances was entertained.

As we stood in formation one morning our sergeant stuttered that he needed two volunteers with “good d,d,driving experience.” Like everyone else in the platoon, I never voluntarily volunteered for anything, but the reference to driving experience was intriguing enough for me to speak up.

Along with Ferdig, the other volunteer who claimed to have driving experience, I found out we would be the designated drivers of the Company’s two jeep-mounted 106 “Recoilless Rifles.”

Deployed to protect the infantry from tanks, the barrel of the top-heavy 106 recoilless cannon ran the whole length of the jeep that it sat uneasily astride. Our crew of four, with me driving, took part in massive “maneuvers” on the rolling hills on the east side of Fort Ord. I was allowed, even required, to drive as fast a possible overland along the steep hillsides while carefully gauging whether the uphill wheels were starting to lift off the ground, lest the top-heavy jeep roll over down the hill.

After I positioned our 106 just below the crest of a hill, the squad leader went to the top and scanned the terrain below for enemy tanks. When he barked “fire mission” I floored the jeep and shot up to the top of the hill, jumped out and positioned myself beside the left front wheel, still holding onto the steering wheel with one hand to be prepared to pull myself back into the idling jeep, while the gunner sited the cannon and the other man in the rear opened the back of the barrel and inserted a huge shell — which made a thunderous blast when we did live firings at targets in the valley below.

We were told we only had about ten seconds to get off a round before the radar on a Russian tank could detect us, so I had to immediately lunge back into the driver’s seat, jam the jeep into reverse with the gas peddle to the floor, and fly blindly backwards down the hill before turning and careening off in another direction.

As drivers, Ferdig and I had unfettered access to the huge pool of jeeps at Fort Ord. We sometimes got jeeps and went joyriding, even driving off-base around Seaside and Monterey.

I hadn’t lied when I said I had driving experience. Growing up in Walnut Creek I’d spent a good deal of time driving various motorized vehicles — starting when I was only twelve with a souped-up “Doodle Bug,” a tiny red motorscooter that could zip along at 35 miles an hour, which seemed really fast only inches above the pavement astride a small seat-cushion and a skimpy tubular frame over a churning five-horse Briggs and Stratton engine and two dolly-sized wheels. I reveled in the surging power at the twist of a wrist as I held onto the handlebars and flew down the road engulfed in the roar of a four-cycle engine. The smell of oil and burning gasoline became intoxicating for me.

Before I was even old enough to get a driver’s license, I bought my first car with money I’d saved from part time jobs — a 1935 Ford five-window coupe with a rumble seat. I had it towed home to my parent’s garage with the intention of getting it overhauled by the time I could legally drive it.

I ended up lovingly taking it completely apart piece by piece, painstakingly cleaning each part in gasoline with my bare hands, and if appropriate, painting the part with colored enamel before re-assembling it. I replaced the old mechanical brakes with newer model hydraulics and smoothed and sanded the body before spraying it with black primer. After pulling the ’35 motor out, I bought a radical, “full load” 1948 Mercury engine block from a hotrodder friend. With the help of various motor manuals I gradually reassembled a complete engine with parts acquired from friends or local wrecking yards. Intent on entering it in drag races I mounted large racing “slicks” on the rear.

By the time my ’35 Ford was “built,” I already had a driver’s license. With some trepidation I finally towed it out of the garage and up to the top of a nearby hill with my father’s station wagon. As I coasted the coupe down the hill I put it into gear and popped the clutch. Vroom! It started right up.

It ran beautifully, but I never got over my nervous surprise at taking it completely apart, rebuilding it, and having it actually run. It struck me as almost miraculous.

I’d only been driving the coupe a short time when someone offered to trade a 1929 Ford, full-fender roadster pickup for it. The roadster was a patchwork of different colors, but I could see its potential.

It was agreed that I could keep the racing slicks off the rear of my ’35. They looked great on the little roadster pickup with its shortened bed and bobbed rear fenders. It already had hydraulic brakes with swing peddles and a ’48 mercury V8 that I outfitted with finned aluminum heads and three Stromberg carburetors (mostly for show, since I only actually hooked up the middle carburetor). I reupholstered the seat and polished up the chrome windshield frame and radiator housing. After going over the body thoroughly I had it painted a deep red. When it was finished I thought it looked good enough to be featured in Hot Rod magazine.

Although my little roadster pickup was not particularly fast, it looked and sounded like it was. The exhaust system could be rerouted around the mufflers into two lengths of three inch sewer pipe. When the plugs were removed from the brass pipes it made a tremendous sound. I reveled in idling slowly out of the High School parking lot, then flooring it after turning onto the straightaway towards downtown. With the lowest geared rear-end Ford ever made and almost no weight over the them, the racing slicks churned up a cloud of burning rubber reminiscent of dragsters coming off the line.

The late fifties was the golden age of automobiles, with all kinds of manifestations, from soaring tail fins to futuristic, aerodynamic shapes. Certain models, mostly older fords, lent themselves to customizing, The various hot rods and custom cars that were created were nothing short of works of art and there was a very strict, if unspoken, aesthetic. Within certain tasteful perimeters, innovations and creativity was encouraged, but some things, such as lowering the rear only, or raising the whole vehicle up, or plastering the body with stick-ons, was frowned upon.

Building custom cars and hot rods provided ample outlet for my artistic inclinations. I also made a little extra money painting images on dashboards and motorcycle gas tanks, in the flaming eyeball school of art. I even did some “striping” with a special brush used to make thin decorative lines and zigzags around the contours of hoods and trunks.

Walnut Creek was at the regional epicenter of the unique car culture that blossomed in the affluent suburbs of 1950’s America. Every Friday and Saturday night a continuous stream of custom cars, from all of the towns in the surrounding suburbs, cruised slowly, bumper to bumper, up and down Main Street, throaty V-8 engines revving, in a long slow line stretching from Hokies Hamburgers at the north end, through downtown to the High School on the south end and back again.

By the time I left Walnut Creek for College at San Jose, I’d fixed up almost a dozen different cars and two motorcycles.

One of the least notable was a ’52 Ford Fairlane hardtop which I lowered all the way around, outfitted with “spinner” hubcaps, and painted a deep purple, with black and white seat covers. With it’s stock six-cylinder engine, I referred to it dismissively as a “pussy” wagon, that was nonetheless reliable transportation.

One day in the school parking lot, my friend Wharton was trying to get his ’50 Oldsmobile coupe to run right and in a fit of anger offered to trade it straight across for my Fairlane. He’d been building that Olds for years, with the ample resources of his father’s auto supply store. It had been completely gone over, with a loaded ’56 engine, a much sought after LaSalle floor-shift transmission, new chrome inside and out, including chromed windowsills, and a beautiful baby-blue and white tuck-and-roll Naugahyde upholstery interior. All it lacked was a good paint job over it’s faded red primer.

After I’d ascertained that Wharton really wanted to trade his Olds for my humble Fairlane, we exchanged pinkslips. Long afterwards I’d see him, with his girlfriend sitting up close to him, cruising in that purple hardtop.