Ho! Grandfather, Grandmother, thank you for this day!

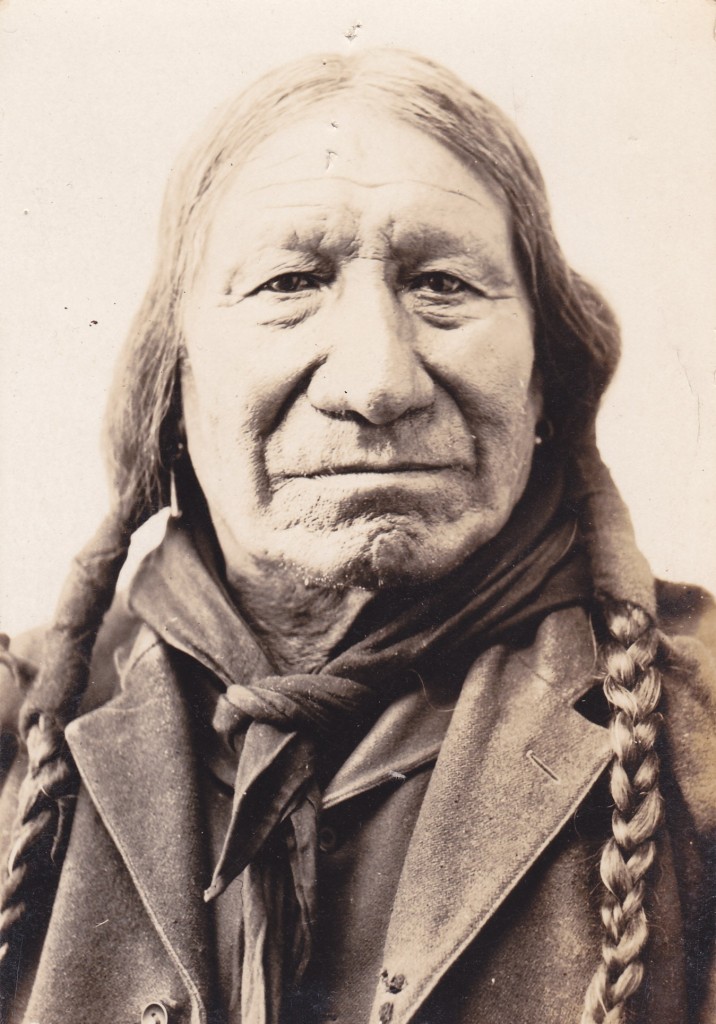

CHIEF AMERICAN HORSE

I was initially unaware of the spiritual significance of the sweat bath. I just liked the remarkable feeling of rejuvenation and freshness produced by the right combination of heat, air and moisture.

Perhaps this propensity was encoded in my genes by the Finnish part of my ancestry. There’s some speculation that the Finnish sauna and the Native American sweat lodge share a common ancestry in the Nomadic tribes of central Asia.

I built my first sauna using an abandoned chicken coop and recycled (scrounged) barn wood, with rough cedar fence boards for lining the interior. Underneath the small, rustic structure, a capped-off steel pipe, with holes drilled along its length, attached to a five gallon propane tank, provided a steady source of heat to a large, heavy steel pan full of rocks that fit into an opening in the floor.

When the hot rocks were splashed with water, a perfect blast of moist, steamy heat, known a “loyly,” or spirit of life, by the Finns, would rise up and fill the sauna.

The sauna was situated behind an old ranch house in the Sacramento Valley, under a huge, one hundred year old fig tree whose leaves reached the ground on all sides like a translucent green dome. A cold water shower attached to a garden hose hanging over a branch completed the picture and soon I was enjoying the camaraderie of communal bathing, as friends and neighbors started showing up for regular sweats.

That first custom-built sauna functioned beautifully for several years. But it had one serious flaw — it didn’t have a thermostat or timer to automatically shut it off. At my own peril I ignored Murphy’s First Law. “If something can go wrong it will.”

Late one night, after taking a sauna, I was awakened by a tremendous whooshing noise, like a jet plane landing in my back yard. I leapt, half asleep, from bed to window.

A monster pillar of fire was shooting about fifty feet straight up into the night sky from where my sauna once stood. The inevitable had finally happened. I’d forgotten to shut off the burner. It had gotten so hot and dry inside that the wood walls had burst into flames. The ensuing heat caused the propane tank to burst open — hence the whooshing pillar-of-fire.

My first impulse was to return to bed. Maybe I could go back to sleep and find out it was just a dream. Instead, I ran, butt-naked, out into the night in a rush of adrenaline, performing superhuman feats of strength and endurance to extinguish the blaze.

Both the early Finns and the American Indians viewed fire as a dangerous element, but one that could be harnessed with the appropriate rituals to produce power and vitality.

The next sauna I built, in the late seventies, employed the lower section of a water heater tank to heat the rocks — with a thermostat that shut it off automatically when it became too hot. Located behind our house in the Santa Cruz Mountains, on a steep bank overlooking the San Lorenzo River, it had a sod roof that sported ferns and other forest plants trailing down the dark redwood exterior. The inside, lined with choice golden brown cedar, was dimly lit by narrow insulated windows. A thick section of a madrone branch supported the ceiling.

I thought I was just making another sauna, but I was to discover that the small womb-like structure I’d built was actually something more — a sweat lodge. No sooner was my new sauna completed, than I was introduced to various devotees of the Native American spiritual path who began showing up for frequent sweats.

Chief among them was Standing Bear. When I first met him he was a pipe-bearer, conducting pipe ceremonies using a beautiful traditional medicine pipe with the name “Kind Heart” carved on the bottom of its red pipestone bowl. He kept it in a large bearskin pipe bag, along with a feather incense fan for smudging with sage and other special objects used in the ceremony.

When he would take out the pipe and raise it to the heavens, the atmosphere seemed to abruptly change.

Bear was a former Catholic (when he was known as Arthur), and he apparently had retained a feeling for ritual. The only other place I’ve experienced such profound reverence was while traveling in Mexico, where I sought out the local village churches for my meditations. I’d sit off to the side near the altar, which was invariably inundated with small offerings and votive candles that cast a halo of dim light over the worn wooden benches and ancient plaster walls. As I gratefully drank in the moment like some rare wine, a pilgrim would come crawling down the aisle to the altar, knees bloody from the distance he had traveled on them.

It’s unusual to witness such deep devotion towards something so intangible and mysterious, especially in a world more concerned with concrete attributes such as what we’ve done and what we own. But from the truly religious perspective, it can be said that we ourselves have never really done anything, much less owned anything.

After carrying the pipe for a time, Bear gave it to someone else, just as it had been given to him. The odd thing was that when he gave away the pipe, it was if he also gave away the energy that went with it. He was suddenly somehow diminished and more subject to the usual human foibles and egotism — as if the pipe had conferred on him a special responsibility and power.

Bear was expert in all kinds of traditional lore. He showed me how to make a water drum, traditionally used in the peyote ceremony, but perfect for playing in the sweat. The edge of a piece of deerskin is formed over marbles, around which a continuous piece of cotton rope is wrapped and tied over the legs of an old three-legged bean pot, to pull the deerskin tight. When the cast iron pot is partially filled with water and the deerskin is wet, these simple drums produce a wonderfully resonant sound when struck with drumsticks fashioned from wooden dowels.

For years we held weekly sweats there on the side of the river and many different people came and went, bringing with them songs and chants from all over, some in English, Lakota, or Navajo, others in no known language.

Sitting cross-legged, the brown walls and bodies only faintly visible in the dense golden light and steam, with the throbbing rhythm of the drums reverberating in my chest and the different voices rising as one, I would remember the old Finnish saying, “In the sauna one must conduct oneself as one would in church.”

Occasionally I traveled with Bear to traditional sweats, in lodges built in the prescribed ritual manner. In these structures, willow branches are bent and tied together to create an igloo-like framework, over which a thick layer of rugs and blankets is laid, with a flap left for entry. In the center a shallow pit is dug, around which aromatic cedar boughs are spread to sit on.

Into this small, low space, as many as fifteen or twenty people are crammed together side by side, sitting with knees against chest, almost in the fetal position.

When the flap is closed, it is pitch black and you can’t even see your own nose. Tactile senses suddenly become very acute. Sounds and smells are heightened.

Outside, rocks are heated in a roaring fire. When the sweat leader calls for them, rocks are rolled into a pit in the center of the sweat lodge with a pitchfork of deer antlers. They are greeted with salutations, like honored guests. Each rock is the size of a human head and so hot they glow white in the darkness. Pinches of cedar are thrown on them, producing little sparks that dance in the darkness like stars, as a pungent woodsy odor instantly permeates the lodge.

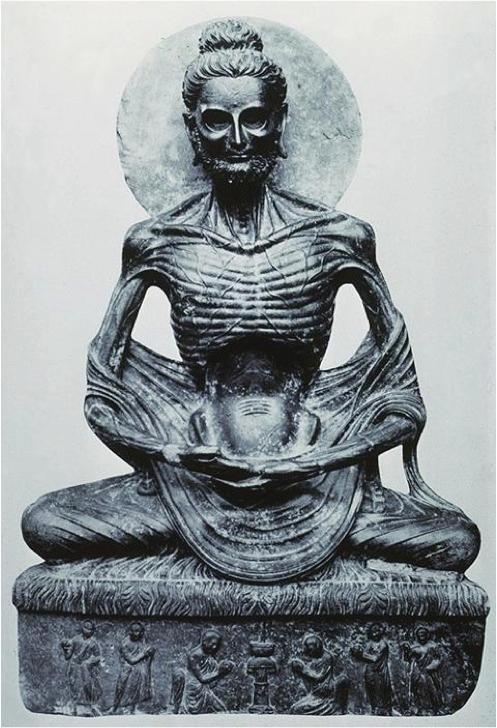

When water is splashed on the rocks, a rush of overpowering heat spreads out and assaults every fiber of one’s being. Sometimes, vainly seeking some cool air, I’d try to bend down near the ground, until I had almost reversed my fetal position. But there would be no escape and finally I’d have to sacrifice body and mind to the relentless heat, melting into a tiny little spark of essence calmly shining in the darkness.

The sweat leader reminds us that suffering is an unavoidable part of life, that the brief pain we experience is in sympathy with the suffering of all beings everywhere. He exhorts us to walk in balance with the earth and the other creatures on it. The Creator is in the creation, not separate. We must show respect and consideration for all of life.

And finally, he asks us to always speak from the heart.

In his native tongue the sweat leader sings an invocation, accompanied by a drum. The other participants are then invited to offer prayers, to seek help for loved ones, or guidance on the path. The prayer moves clockwise around the sweat lodge, as one by one each voice cuts through the burning darkness.

Always there is someone who goes on at length, until suddenly their voice chokes with emotion and a wave of healing tears sweeps silently through the lodge.

Between rounds the flap is opened and fresh air and light stream in. If anyone needs to go out, this is their chance to leave. No one moves. More rocks are called for and there is another round of sweating, singing and praying.

After a last round, glowing bodies finally emerge from the dark, moist interior of the sweat lodge, as if from the womb of Mother Earth herself, purified and cleansed — reborn.

*This piece first appeared in Coast Magazine in 1996.